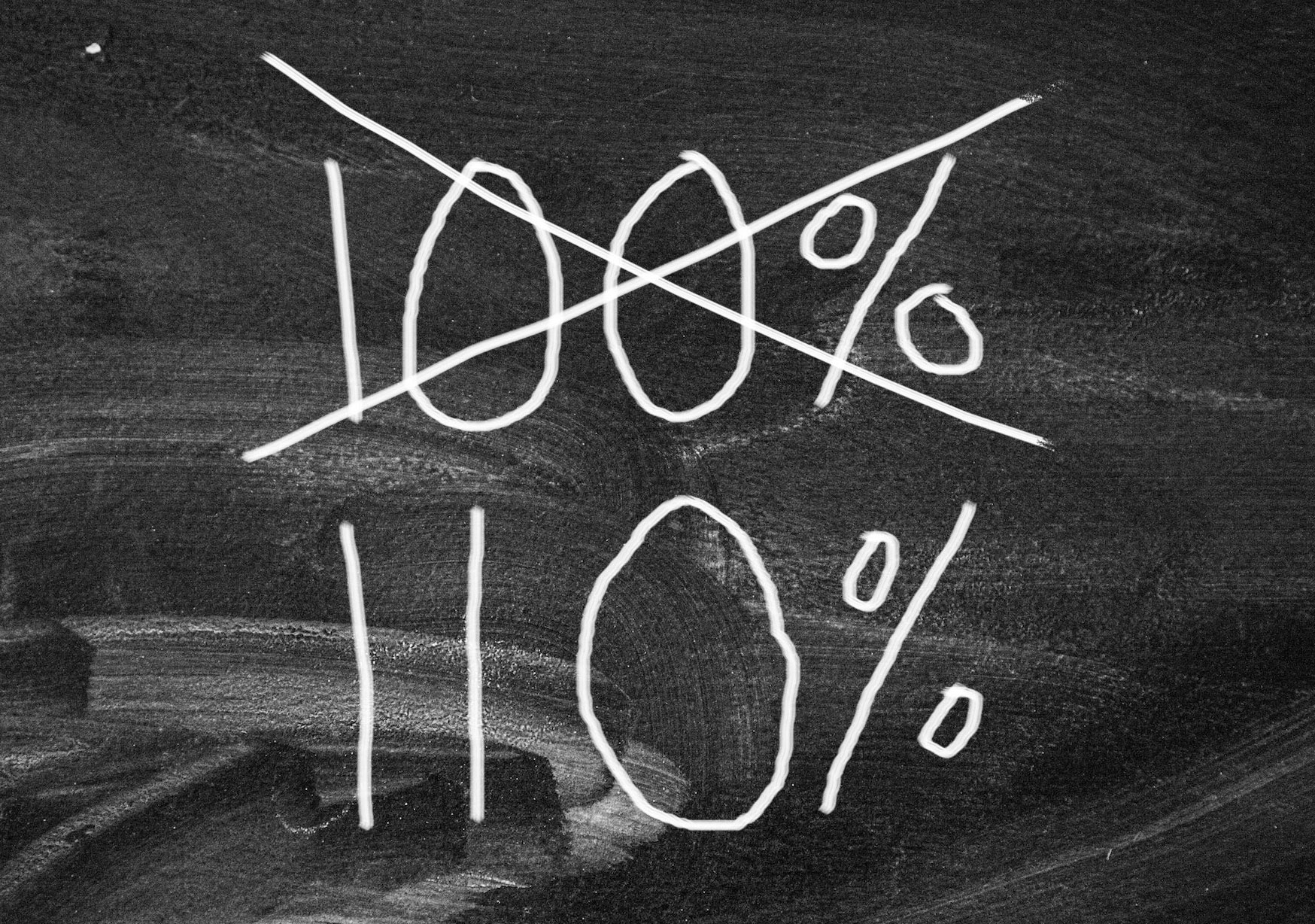

110% inheritance tax: Compensating for privilege

As we have seen in previous articles on this blog,

-

- there is strong ideological ground from a meritocratic, social-liberal perspective for high inheritance taxes

-

- there is strong empirical evidence signalling a rebirth of feudalistic elements in our modern societies which call for action

-

- the reservations against inheritance taxes are largely groundless

If this is the case, the question is not, do we need very high inheritance taxes, but rather, how high should they be? 100%?

If we acknowledge the fact laid out in the article on social-cultural feudalism that inheritance of privilege goes far beyond the mere economic inheritance of money and other property, we should come to see that a confiscatory tax rate of 100% would not suffice to do away with all inherited privilege. It would only eradicate economic inheritance. Structural advantages through upbringing, education, network, social status, will remain. But we cannot or may not want to interfere in these private domains too much as society and state. Taxing wealth is a rather simple, technical act. Trying to equalise sociocultural privilege is something very different.

So if we have to accept that a significant degree socio-cultural privilege will remain even if we take away the monetary privilege through 100% inheritance tax, how can we still achieve somewhat equal opportunities for all members of society? One way would be to increase tax rates beyond 100% in order to compensate monetarily for the non-monetary benefits one inherits.

Let’s fist look at how a potential 100% inheritance tax system could look like, and then compare it with a system with inheritance tax rates beyond 100%. Please note that in this article we are not going to discuss and refute the various arguments against (high) inheritance tax rates, as this has been done elsewhere. This arti le in particular deals with how a 100 or 110% percent inheritance tax regime could look like and how such regimes relate to the goal of creating equal opportunities.

100% inheritance tax: Tackling most economic privileges

How could a system of 100% inheritance rate look like? I would have to pay the equivalent value of the property I inherit (e.g. landed property or company shares) in inheritance taxes to the state. Not all at once, this can happen over long timeframes with generous tax deferrals, and very moderate interest rates. You basically take up a tax liability at the state in order to purchase your inherited property. Just like anybody else who would take up a loan to buy a house or take over company shares. It thus enables a person to take over an estate without overly privileging the person compared to somebody who doesn’t inherit anything.

By accepting the inheritance (you could also say no, see below) you make the decision that you will payback the tax liability overtime, e.g. through the expected returns from the property. This could be distributed profit from the company shares, rental income from the landed property, or simply the sale of the assets.

If you don’t accept an inheritance (e.g. because you don’t feel comfortable with the big tax liability and the risk of a personal insolvency or because you simply don’t want to be associated with it and its responsibilities), the property could either fall to the state or you could donate to a charitable purpose.

Does 100% inheritance take away all monetary privileges? It would seem so at first sight, as 100% are 100% right? But if we look more closely, we can see that by granting somebody a loan (tax liability) with long deferral options and very moderate interest rates, this is already a considerable privilege. To illustrate this, let us compare the following two fictive cases:

-

- Peter is 32 years old, a trained carpenter, with more than 10 years of work experience in some local carpentry businesses. He would love to manage his own company and become an entrepreneur. He has many business ideas, within carpentry and beyond. He goes to different banks to pitch them his ideas for his own startup to get seed funding. When he fails, he asks for a loan to take over an existing carpentry business that is struggling with the structural changes of the IT revolution, and that he would like to turn around and make fit for the future. He fails again, because of low credit worthiness, because he didn’t inherit any wealth, and his savings from his young career are low. He continues to work as an employed carpenter, until he becomes unemployed because of the continuous mechanisation and automation in the carpentry business. He struggles.

-

- Just like Peter, Sylvia is 32 years old, is a carpenter and worked as a such for some 10+ years. She is also entrepreneurial, but different than Peter she actually comes from a family business background, so she inherits the company shares when her father dies. She decides to accept the inheritance and with it the 100% inheritance tax liability. She manages the company well, grows it, and by her mid-40s managed to payback all the tax debt. She sells the company and retires early with considerable wealth.

Despite 100% inheritance tax, Sylvia benefitted from the privilege of being able to take over company ownership through accepting her inheritance, whereas Peter wasn’t offered this chance. He had to try with banks, and failed. Even if he had managed to get a loan, it would have come with high interest rates and tighter repayment agreements than what Sylvia was offered by the state through the inheritance taxation.

It is important to note that of course, we could envision an inheritance tax liability system with more market-like interest rates and repayment agreements. We could even envision a system where inheritance is not guaranteed, but you have to apply for the inheritance tax debt just like with a bank, and when your creditworthiness is not good enough, you would not be granted the tax debt. While this would increase equality of opportunity, it may prevent family business succession or the transfer of property with intrinsic value to the family (e.g. the family home) to a considerable degree. Here, equality of opportunity would potentially conflict more strongly with other targets.

We can summarise that a 100% inheritance system may or may not wipe out all economic privilege. If you treat heirs preferentially when it comes to tax liability (with long deferral times, moderate interest rates and no creditworthiness checks), some economic privilege remains even when heirs have to pay 100% inheritance tax.

110% inheritance tax or more: Against the remaining privileges

No matter if a 100% inheritance system would wipe out all economic privilege or not, the socio-cultural privileges usually associated with monetary privileges will remain in either case. In order to cater for the potential remaining monetary privileges and for the non-monetary privileges, an inheritance tax rate beyond 100% is conceivable.

Such a tax rate beyond 100% (we may call it a compensatory inheritance tax rate) could be perceived as something similar to a handicap in sport: “the practice of assigning advantage through scoring compensation or other advantage given to different contestants to equalize the chances of winning.”[1] In the case of compensatory tax rates, handicapping would be achieved by financially disadvantaging the otherwise excessively advantaged.

It is not uncommon to treat advantaged and disadvantaged population groups differently and actively favour the latter over the former to equalise opportunities. Under the concept of affirmative action we already employ such positive discrimination practices when it comes to

-

- Employment or enrolment quotas in jobs or educational institutions for women, people of colour, and other disadvantaged groups

-

- Financial subsidies or scholarships to disadvantaged population groups

-

- Preferential treatment, e.g. for hiring, if otherwise similar qualification, for disadvantaged groups

-

- Financial aid for disabled people

-

- Equal access policies for disabled people

In a wider sense, our social security systems and progressive tax systems could in general also be regarded as discriminating positively towards the disadvantaged: I only enjoy unemployment benefits if I am disadvantaged enough to be unemployed. I pay zero or little income tax if I am disadvantaged and have little income.

Applying compensatory inheritance tax rates of 110% may thus not be such an outrageous idea as it may seem to some at first. It is just another form of handicap, affirmative action, and positive discrimination that we already apply elsewhere in our societies. Meritocratic principles guide all these interventions: We want to reward effort, not chance, and create level playing fields in which everyone has incentives to give their best.

Technically, compensatory inheritance tax rates could be handled as a tax liability that can be paid back to the state over long-time periods with moderate interest, just like in the case of a confiscatory rate of 100%. 110% inheritance tax would technically be not much different than 100%, or even the currently common rates of 20, 30, 40%.

In any sports, we find it completely fair and utterly necessary that we design systems in which players/teams have roughly similar chances of winning and compete on a level playing field. Games in which some players have way higher chances of winning than others we perceive as boring, unfair, and not sportsmen-like. It is time that we become brave enough to cultivate this sense of fairness that we seem to have in sports and apply it to the race of live: giving everybody equal opportunities by favouring the disadvantaged and handicapping the advantaged.

Further Reading

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Handicapping

[2] Chowdhury et al. (2022): “Heterogeneity, leveling the playing field, and affirmative action in contests”. https://doi.org/10.1002/soej.12618

[3] Brown and Chowdhury (2017): “The hidden perils of affirmative action: Sabotage in handicap contests”. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2016.11.009