Against Majority Opinion? Equality of Opportunity as a Constitutional Right

Inheritance taxes are highly unpopular and on global retreat. Country after country is reducing the tax or abolishing it altogether. Politicians supporting this direction are celebrated and successful. Even wealth taxes are more popular than inheritance tax, despite being economically less meaningful and morally more difficult to defend. In short: inheritance tax is a hated tax, a majority of people does not want it (to be increased).

There is two ways to acknowledge that inheritance tax is unpopular and still uphold the claim to increase it. First, it may be that current public opinion is biased, uninformed and/or irrational in the sense that it does not reflect the interest of the population. In these cases, there could be hope for changing public opinion to support inheritance taxes. The second option is to justify the need for inheritance taxes irrespective of any majority opinion.

Changing public opinion

It is a fact that public opinion is not in favour of inheritance taxes across large parts of the globe. However, research has shown that if you inform people about the relevance of inheritance, they become more supportive of inheritance taxes.[1] Many people know relatively little about inheritance flows, who actually has to pay inheritance tax (a tiny fraction of people) and the socio- economic relevance. This lack of knowledge may partially arise because of the low visibility and secrecy around large-scale inheritance.

On top of informing people about inheritance, the framing of inheritance and inheritance taxes may also matter for public opinion. There is a solid amount of evidence on the very strong campaigning efforts of narrow interest groups that successfully influenced the narratives around inheritance in many countries.[2] Public opinion may thus be altered if politicians or pro-tax interest groups apply equally strong campaigning to correct the narrative that high inheritance tax actually benefit the vast majority, only affect a minority, and that it will not cost jobs and make SMEs go bankrupt.

In line with the framing and campaigning efforts of special interest groups, the media has been found to play its role as well by being biased. Scholars have discovered deficits in three core areas when it comes to the coverage of the inheritance tax debate: 1) intensity of coverage, 2) content, 3) voices heard.[3] It is found that anti-tax voices are much louder than pro-tax opinions. It has to be questioned whether this must be attributed as a media failure or a failure of the weaker, less-funded, less organised pro-tax community.

Lastly, public opinion on inheritance tax may not only be determined by information and narratives, but also by issues concerning trust. People may know that its primarily the super-wealthy who are affected by inheritance taxes and they may be smart enough not to believe in the framed narratives of the anti-tax lobby, but they may still be against inheritance tax if they fail to trust that the superrich will actually pay their fair share. Rightfully, some people may be sceptical of increasing inheritance taxes as long as so many legal and illegal loopholes exist. Closing the loopholes would be a promising approach to win the support of generally supportive voices in society.

Equality of opportunity as a constitutional right

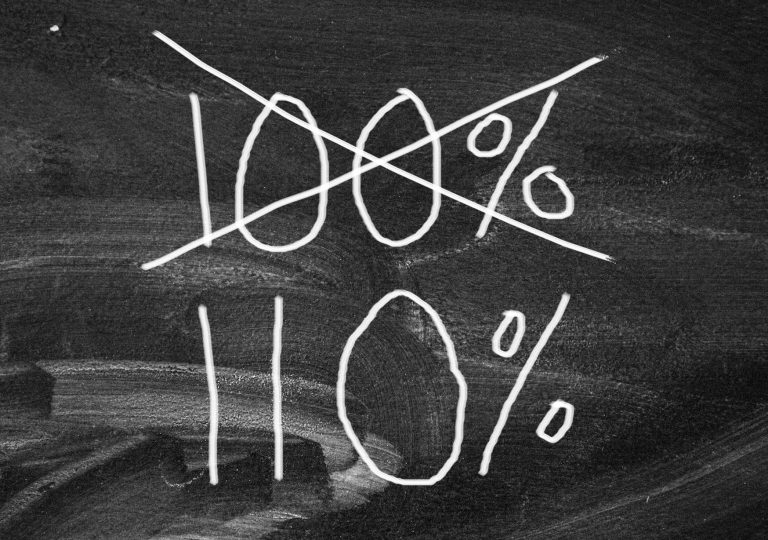

However, what if attempts to change public opinion fail, and a majority of people continue to support inheritance? Even in this case, inheritance taxes may be called for. A majority opinion is not a necessary precondition for high inheritance taxes or the abolition of inheritance. In a constitutional state, do we ask the majority of people what they think about the death penalty, about minority rights, about human dignity? No, instead we have agreed on a certain set of unconditional, unalterable constitutional rights. No tyranny of a majority can ignore them and terrorise a minority or disrespect fundamental human rights. In this sense, a liberal democracy is more than majority rule.

It is in this light that equality of opportunity needs to be considered as a constitutional right, or a right that follows straight from the most basic constitutional rights. According to many liberal constitutions, humans are born equal, free and with human dignity. If we are born equal, we must be born equal in opportunities. How can we speak about being born equal if one baby is born as a millionaire and the other in debt?[4]

Equality of opportunity can not only be deducted from the constitutional principle of equality, but must also be perceived as a fundamental expression of liberty. A liberal society protects equality of opportunity. Freedom is always relative and can only be defined in relation to others. Distributing opportunities unevenly to (new) members of society increases the freedom of one party at the expense of the freedom of another party. How large is my freedom if other members of society start their life with an insurmountable advantage? How free am I if however hard I try, I will not be able to catchup?[5]

Last but not least, the constitutional protection of human dignity prescribes equality of opportunity. Inequality of opportunity is an infringement of equal human worth and rights. How can dignified self-esteem arise if I am not granted the same opportunities in life than my fellow members in society?[6]

The next evolution of our constitutions

As we have seen, constitutional rights protecting human dignity, liberty and equality also call for equality of opportunity. If constitutional rights protect equality of opportunity, they should prohibit inheritance. Inheritance means passing on privilege across generations and perpetuating inequality. Inherited privilege thus needs to be restricted to a degree where it has a negligible effect on equality of opportunity, or it needs to be abolished altogether.

If equality of opportunity can be deducted from fundamental constitutional rights, then we should aim for the abolishment of inheritance irrespective of majority opinion. The gradual historical extension of fundamental rights and equal treatment such as those of women or racial and sexual minorities were usually not put up for vote or referendum. Rather, they were pushed by minority activists and ultimately enacted by legal or political systems realising the need for change. Abolishing inheritance due to its adverse affect on equality of opportunity may thus be the next evolutionary step of our liberal, constitutional democracies.

Further Reading

[1] Bastani and Waldenström (2021): “Perceptions of Inherited Wealth and the Support for Inheritance Taxation”. Economica Volume 88, Issue 350. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecca.12359

[2] Prabhakar (2018): „Why do the Public Oppose Inheritance Taxes?“ In: Gaisbauer, Helmut P.; Schweiger, Gottfried and Sedmak, Clemens eds. Philosophical Explorations of Justice and Taxation: National and Global Issues. Ius Gentium: Comparative Perspectives on Law and Justice (40). Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 151–166. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-13458-1_10

[3] Theine and Grisold (2020): „Streitfall Vermögenssteuer- Defizite in der Medienberichterstattung.“ https://d-nb.info/1220788295/34

[4] Some constitutions explicitly work with the terminus equality of opportunity, such as India’s. https://www.constitutionofindia.net/constitution_of_india/16/articles/Article%2016

[5] For a review of how liberal and even libertarian values can call for 100% inheritance tax, see Bird-Pollan (2013): „Death, Taxes, and Property (Rights): Nozick, Libertarianism, and the Estate Tax“. 66 Maine L. Rev. 1 https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2367774

[6] For a discussion of human dignity in relation to inequality and wealth, see Neuhäuser (2018): „Reichtum als moralisches Problem“. Suhrkamp