Meritocracy, Handicap and Free Will

In any debate about taxation, the concept of meritocracy is central: the distribution of income and power according to merit, that is, performance and achievements. It is also a central liberal concept and thus of importance to this text which argues from a social-liberal perspective. Meritocracy is a popular and influential concept and can serve to justify both inequality itself as well as equalising re-distribution measures. The interesting thing that makes meritocracy also quite complex is that merit – if your really think the concept through – is not about measurable output or achievement alone. It must also consider the input. When applied to the context of human work and income, this means, it also considers the talents and other predispositions that influence the outcome.

Effort and handicap

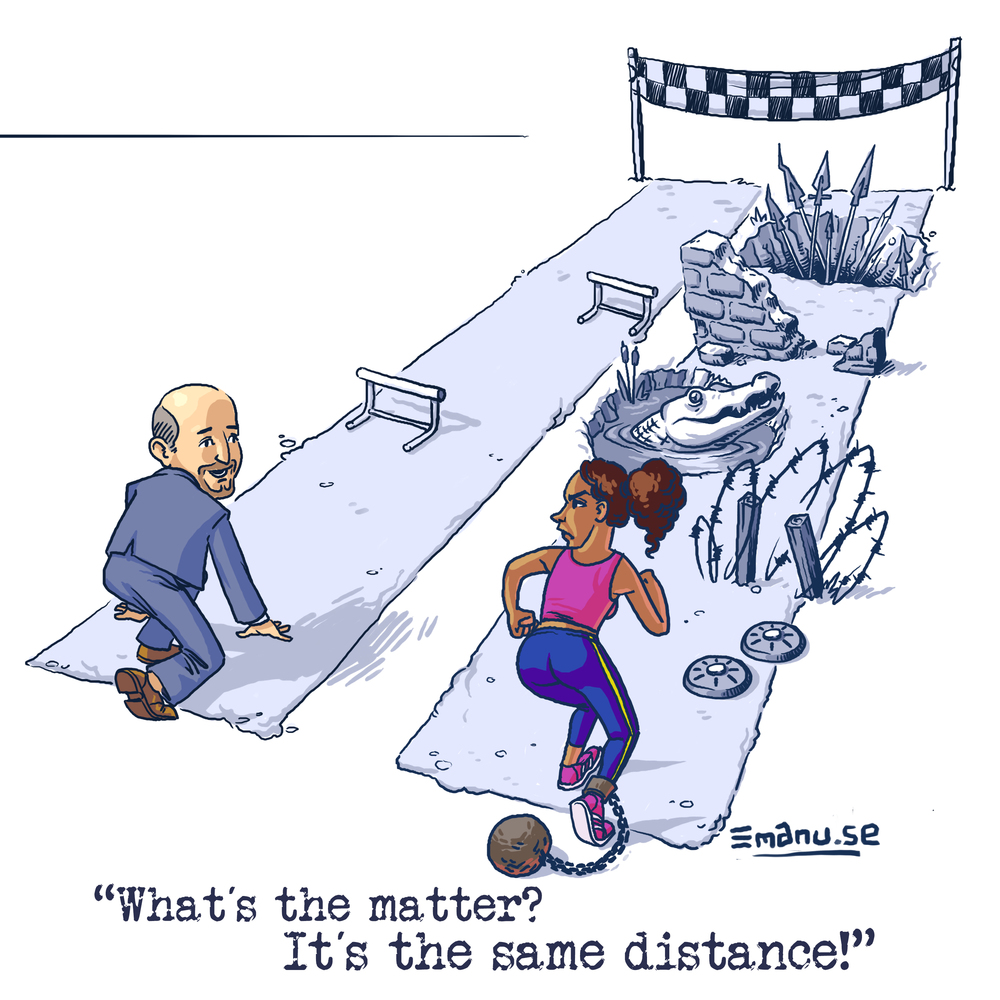

Let’s take an example: Whilst travelling the world you have a bus accident in the desert. You are with your three very young kids, and need to carry all three of them on your shoulders and arms through the desert until you reach the next town and water supply. You nearly collapse, but you make it. A great performance indeed. But shortly after arriving you see a very old man carrying his three small grandchildren, just like you did. But he is much weaker due to his age. He still managed just like you did. But wasn’t his achievement larger? Both of you carried the same weight through the desert, but he had worse preconditions. He had to bring up even larger effort than you, overcome even more pain.

So we can see that we don’t only look at outcome and performance but also to the conditions and the actual effort that needs to be put into something when judging about merit. That’s why in sports we have different evaluation classes for male vs. female, for different weights, different age groups, etc.. In golf and some other sports, we have the beautiful concept of handicap which is the practice to “equalize the chances of winning” [1] in order to “enable players of varying abilities to compete against one another”. [2] Let us call this remarkable institution the ‘handicap principle’. As it is about equalising the chances of winning, the handicap principle is really in essence about equality of opportunity. In order to achieve a fun and fair game, scoring is corrected for the players’ predispositions. Not the objectively better one wins the competition, but the one who has -given his skills, prior training, etc. – shown the relatively better performance.

To a limited extent, we also apply the handicap principle to real life and our political and economic institutions, e.g. by providing social security and unemployment benefits (which can be read as an acknowledgement that somebody is not unemployed because of a lack of effort but because of unfortunate circumstances) or by progressive taxation schemes which tax higher incomes at higher tax rates (can be read as an acknowledgement that more successful people might have had easier starting positions so that its only fair to have them contribute more to society). When it comes to inheritance, there is little application of the handicap principle: Instead of trying to create equal starting positions in the race of life, we allow for tremendous differences in initial endowments so that the resulting socio-economic competition (if you may want to reduce our lives to this) is unfair and biased from the beginning.

A free will?

So far, so good. Or bad, actually. But it comes worse. Or at least: more complicated. We established that merit is about effort, not about measurable output alone. Merit is what happens between input and output. So what determines my efforts? What determines whether I turn the input, predispositions, and constraints that I face into a lower or higher output? Well, you might say, “that’s your choice! It’s up to you to decide how much effort you will put into it!” This leads us to an essential element of merit: my own choice, or better: my free will. It is because I can choose to make an effort that people will value my merit based on that. In fact: Because effort is the only thing I can choose (I can’t choose my predispositions, my talents, etc.), it is the only thing I can be accountable for. Because I have a choice, I can be accountable, and I can gain merit if I choose to make an effort.

But, what if I can’t choose freely? What if what appears as my free choice is actually influenced by something I don’t have control over? It is doubtful whether the concept of effort and merit would still have meaning in this case. Given that there is serious debates with contributors from psychology, neuroscience and philosophy on the existence of free will, it appears at least save to say that free will is at best limited and that quite a number of choices we make are not free and conscious but shaped by our subconsciousness, our genes, our socialisation and education (for which we are only partially responsible).

Up with meritocracy

It’s interesting to note that the term meritocracy itself was coined by the sociologist Michael Young with a very negative connotation in his dystopian book “The rise of the meritocracy” in which he criticises a stratified society that is overly based on merit. In reference to his original critique and the ironically positive association and career in the business context the term and concept have achieved, Young felt the need to write a comment on this in the Guardian in 2001 titled “Down with meritocracy” in which he held:

“It is good sense to appoint individual people to jobs on their merit. It is the opposite when those who are judged to have merit of a particular kind harden into a new social class without room in it for others.” [3]

He thus does acknowledge here – more clearly perhaps than in his original book – the general positive effects and desirability of meritocracy. But he primarily uses the comment to warn about the overseen dangers that come with it. Given the above thoughts, this text is largely in agreement with Young on both parts. We established before that merit is based on true effort, and wherever such true effort exists, rewarding people based on merit appears to be justified from a meritocratic philosophy. But where either my physical or my mental ability to perform are limited by factors I cannot consciously influence, we can not speak of merit and shouldn’t reward or punish my behaviour based on that.

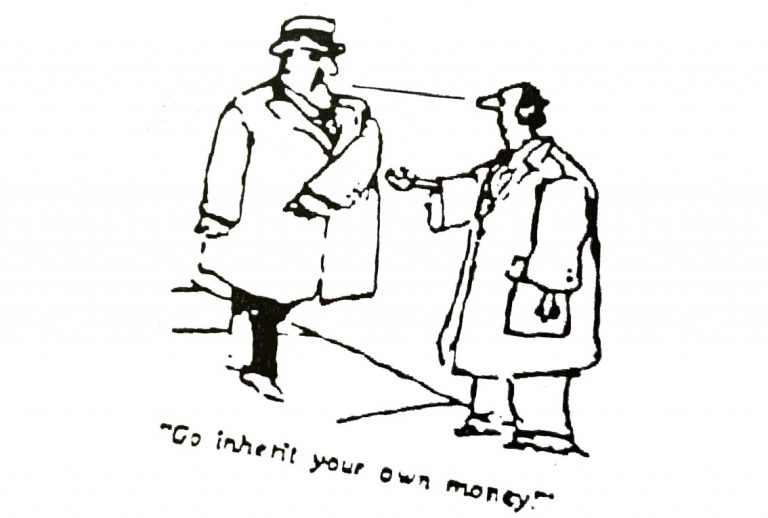

So just like Young acknowledged, appointing individual people to certain jobs (and income) based on merit is justified, if the mentioned limitations are accounted for in assessing ones merit. This means meritocracy can not only justify inequality (as often done by neoliberals, it can also justify taxing high salaries very progressively and other welfare state means such as a socially-oriented education system (not the kind of elitist education system Young was actually in opposition to) to level-out the differences in predispositions, so that true effort can be revealed. With regards to Young’s comment on hardening a social class of those having merit, this goes well in line with our earlier notion that meritocracy and inheritance are – well, inherently – incompatible. Inheritance is income without merit. That is why inheritance taxes are much more compatible (or even called for) from a meritocratic standpoint than income or wealth taxes, even though we have laid out some arguments above while even the latter may be in line with meritocracy. In contrast to Young’s dystopian notion and also other modern criticisms such as “The meritocracy trap” by Daniel Markovits [4] or “The tyranny of merit” by Michael Sandel [5], it may thus indeed be possible to hold up a positive view of meritocracy. It seems what meritocracy-skeptics are critical about is not really meritocracy itself, but rather an elitist and feudal system that covers up under the disguise of meritocracy. Meritocracy, when taken serious, can be a good thing. It just needs the application of the handicap principle which is all about equality of opportunity. It needs an interpretation of merit as true effort, taking limitations and predispositions into account. Meritocracy of this kind should be embraced and can form a great building block of socialliberalist thought.

Further Reading

3. Guardian Article by Michael Young “Down with meritocracy”: https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2001/jun/29/comment