Meritocracy: As far as our talents and hard work takes us?

In “The Tyranny of Merit”, Michael Sandel exposes some of the problematic aspects of meritocracy, or at least the version of meritocracy applied in the US and some other Western countries such as the UK or Germany. In a nutshell, Sandel holds that meritocracy can lead to hubris among those who succeed in formally meritocratic societies, as well as humiliation for the losers in a meritocratic race. If everyone believes that success is only dependent on hard work and talent, then the winners can rightfully claim they have worked harder or are more talented than the rest. Similarly, the losers have no one else to blame but their own laziness or lack of talent, which leaves them in a pathetic state. This meritocratic dynamic, according to Sandel, would fuel the erosion of solidarity and the notion of a common good and spur resentment against the system and elites, such as visible in Trumpist America or Brexit UK. Further inspection of Sandel’s critique reveals that it is really not meritocracy per se that he has a problem with, but some neo-liberalism that appears to come with it:

“Global supply chains, capital flows, and the cosmopolitan identities they fostered made us less reliant on our fellow citizens, less grateful for the work they do, and less open to the claims of solidarity. Meritocratic sorting taught us that our success is our own doing, and so eroded our sense of indebtedness. […] To renew the dignity of work, we must repair the social bonds the age of merit has undone.”

Michael Sandel, “The tyranny of merit”

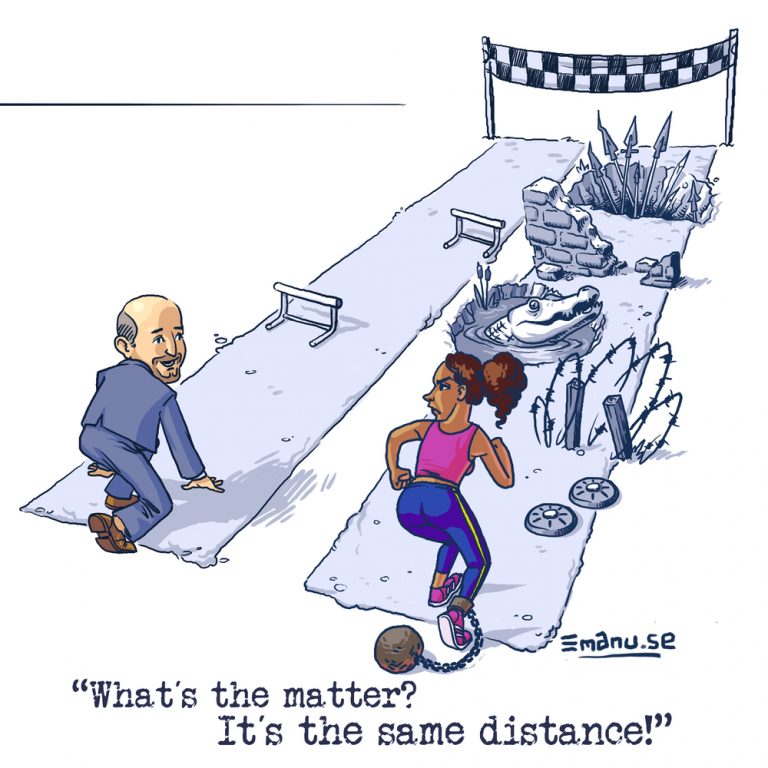

It is possible to share Sandel’s well-grounded and formulated critique and still uphold meritocracy as a desirable concept. But for that, we need to be precise about the definition of meritocracy and what we really mean by the term. Sandel defines it as a system “in which everyone has an equal chance to rise as far as their talent and hard work [emphasis added} will take them”. This definition is in line with the popular usage of the concept, as can be seen in the many references Sandel makes to presidential talks, which apply the “as far as your talent and hard work will take you” motive from both conservative as well as liberal US presidents. However, the definition is problematic. Talent and hard work are two very different things in the context of meritocracy, and shouldn’t be subsumed as the essence of meritocracy. It is puzzling that both in research as well as popular conception talent and hard work are often conflated when talking about meritocracy. It can be argued that a purer conception of meritocracy that is more true to the word should focus on hard work and effort, leaving talent aside. After all, meritocracy as a concept is really all about the “everybody can make it” part (through hark word) rather than the “if you are lucky” part (talent).

Wouldn’t Sandel’s critique of hubris among winners and humiliation among losers still apply, even if we took out talent from the definition of meritocracy? Yes, it would, even more so. But the key point is: If we understand meritocracy as a state of fully equal opportunities, we realise that this is impossible and will never be achieved, as there will always be elements of luck and factors beyond our own control affecting our opportunities. As we shall discuss at a later stage, even if it would be possible to measure natural differences such as talent or IQ and attempt to equalise those different opportunities e.g. by a monetary handicap for the more privileged, it is by no means clear whether such state intervention is desirable. Even if it would be possible and desirable to equalise opportunities at the start of life, how could we possibly wipe out any element of luck during the process of life so as to ensure that success is really only dependent on our own doing? It seems to be an impossible project.

We need to accept that full meritocracy in the pure form (effort-focussed) cannot be achieved. We cannot be sure if our success is solely our own doing because our free will is limited, our talents are inherited, and we don’t control the many other factors around us that determine whether we are successful or not. Therefore, no matter how egalitarian and meritocratic a society we live in, no matter how hard we work and how successful we are, we will always have to hold up a certain degree of modesty, indebtedness, thankfulness and sense of community and solidarity. This line of thought is very compatible with Sandel’s reasoning and what he calls for. But deviating from Sandel, there is no need to diagnose a tyranny of merit and do away with meritocracy. We can keep it as a northern star that we are striving for as a society, knowing that we will never reach it and- maybe more importantly- that we don’t need to because of the beauty that lies in being contingent and thus connected to our fellow citizens. Meritocracy of this kind should be embraced and can form a great building block of social-liberalist thought.

Further Reading

Sandel (2021) “The Tyranny of Merit. What’s Become of the Common Good?”, Picador.

Markovits (2020): “The meritocracy trap”. Penguin.

Friedman et al. (2023): “The Meaning of Merit: Talent versus Hard Work Legitimacy”. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/soad131