Equality of Opportunity and Equality of Outcome: It’s just not the same thing!

The key concept of social-liberalism is equality of opportunity. It rests on the insight that true liberty can only be achieved through fairness: How can I be called free if I start off my life with a tremendous disadvantage compared to somebody else, be it skill-wise, health-wise or in terms of wealth? If I am destined not to be able to catchup (or if its highly, highly unlikely), can I then be called free? If we perceive freedom as opportunities, shouldn’t those opportunities be distributed as even as possible to allow a maximum degree or freedom for everyone?

Equality, Freedom, Dignity

Despite all innate differences of humans, most modern constitutions proclaim that men and women are born equal, free and with human dignity. Equality of opportunity follows straight from these three basic constitutional principles, as can be seen below:

- Equality: This is probably the most obvious. If we are born equal, we must be born equal in opportunities. How can we speak about being born equal if one baby is born as a millionaire and the other in debt?

- Liberty: Equality of opportunity is also a fundamental expression of liberty. A liberal society should thus protect equality of opportunity, because freedom is most often a relative construction. This means, my freedom is constituted in relation to your freedom. Distributing opportunities unevenly to (new) members of society increases the freedom [1]of one party at the expense of another party. How large is my freedom if other members of society start their life with an insurmountable advantage? How free am I if however hard I try, I will not be able to catchup? Besides, freedom is also about voluntary decisions and exchange, but no one is asked to be more over- or underprivileged.

- Dignity: Lastly, human dignity also prescribes equality of opportunity. Inequality of opportunity is an infringement of equal human worth and rights. How can dignified self-esteem arise if I am not granted the same opportunities in life than my fellow members in society?[2]

We can see how equal opportunity follows from these three constitutional rights, but will focus particularly on the second (liberty principle), as it tends to be underrepresented in the debate despite making quite a powerful argument.

Liberalism and Inheritance

Equality of opportunity doesn’t go too well with inheritance. Inheritance essentially means passing on privilege across generations and perpetuating inequality. Inherited privilege thus needs to be restricted to a degree where it has a negligible effect on equality of opportunity or abolished altogether. Privilege can be inherited economically (by passing on financial wealth), socially (e.g. through access to a favourable network) or culturally (e.g. through education).[3] Social and cultural inheritance and the resulting inequalities are more difficult to control, so limiting economic inheritance needs to be the focus of any society seeking to maximise equality of opportunity. It is also questionable if society should interfere too much into cultural and social inheritance (such as socialisation) beyond offering a good and accessible public early childhood care and school system. It is way less problematic for the state to interfere in economic inheritance.

One of the most influential writers on equality of opportunity was John Rawls. The concept is central to his work. In his ‘Theory of Justice’ he calls for inheritance taxes as a means to create equality of opportunity. Rawls defined three principles in his book, all of which are consistent with inheritance taxes, as can be seen from the following: Inheritance taxes i) defend political liberties by reducing the undue influence of the wealthy (liberty principle), ii) create more equal starting positions in life (fair equality of opportunity principle) and iii) minimise inequalities to a level still compatible with the greatest possible wealth for the least advantaged (difference principle). While the first two principles allow or even call for unlimited inheritance taxes, the third principle may prohibit high inheritance tax rates if they would decrease the overall output substantially (which is by no means a given). Overall, high inheritance tax rates seem very much in line with Rawlsian equality of opportunity, especially when the.tax returns are used to benefit the least advantaged e.g. through a basic inheritance.

That equalising opportunities through inheritance taxes is in line with fundamental liberal values has even been recognised by hardcore libertarians like Robert Nozick, who towards the end of his life came to realise and recommend 100% inheritance tax on second-generation inheritance, while leaving the “self-earned” wealth of the inheritor untouched. This, to me, seems to be a half-hearted compromise of his late realisation about the incompatibility of inheritance and freedom with his prior writing. In order not to contradict himself too much, and to rescue the idea of just possessions that shouldn’t be taken away by anyone involuntarily, he proposes this inconsistent version of a confiscatory inheritance tax.

Scholars after Nozick were able to overcome his compromise proposal and reconcile his libertarian ideology with a full 100% inheritance tax even on “self-earned” wealth. The argument here goes like this: If Nozick and other libertarians care so much about the free transactions between individuals that lead to a certain outcome that according to them must be called just (because it was based on voluntary transactions), then how is this view compatible with inheritance? After all, people who receive no inheritance have not agreed to this disadvantaged ‘initial distribution’ (in Nozick terms). Of course, it may be a voluntary decision by the deceased party to transfer his wealth to another party, but property rights cease to exist upon death, so what matters is the perspective of the receiving party. Because we cannot speak of voluntary transactions or consent by all parties if we look at the situation from the perspective of each new generation, we must reject inheritance from a liberal (or even libertarian) perspective.

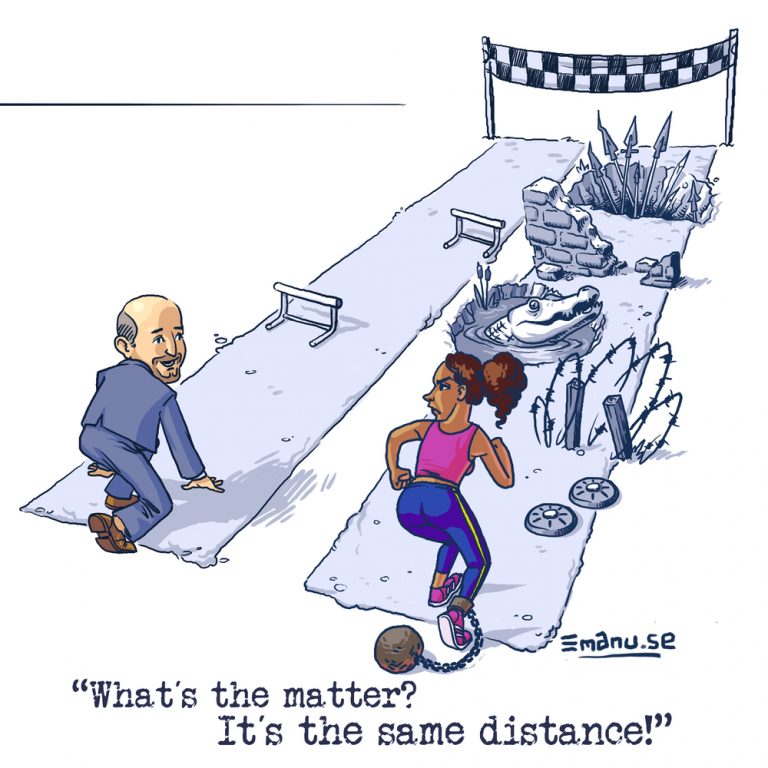

It’s not about equality of outcome

Equality of opportunity is explicitly not about equality of outcome. It is a liberal concept in that it calls for the abolition of privilege, but explicitly acknowledges that a liberal and diverse society is characterised by a healthy degree of inequality. Healthy to the extent that it is the result of freedom of will, and chance. Against all psychological and neuroscientific insights questioning the autonomy in human decision-making, a liberal society must assume that there is a minimum level of free will in humans. Where there is free will, there is room for choice, error and success. Paired with chance, a society with unequal economic, social and cultural outcomes is unavoidable, and can still be in line with equality of opportunity. Just as in sports, winners and losers can both be happy if the game was fair, in the sense that chances of winning were similar for all players.

A liberal society should seek to maximise equality of opportunity by abolishing inheritance, but be more cautious about taxing income or wealth. Inheritance tax is liberal in nature in that it creates equal opportunities and does not punish merit. Also, inheritance taxes do not take anyone’s property away against their will (as property rights cease after the death of a person like all other rights do). Income and wealth taxes are the opposite: They take away property against somebodies will, and they do punish merit. This is not to say there is no need for income taxes at all, but just to make clear that from a social-liberal perspective, inheritance taxes are by far to be preferred over other forms of taxation. The proceeds of inheritance taxes may consequently be used to lower income taxes and to avoid wealth taxes.

Social-liberalism aims to maximise equality of opportunity, but not equality of outcome. It is in this key differentiation from egalitarian or socialist ideologies that social-liberalism draws its strength and may be able to mobilise support both from left and conservative sides of the political spectrum.

Further Reading

[1] Chistian Neuhäuser, “Reichtum als moralisches Problem”, Suhrkamp. 2018

[2] Rawls (1999): “A Theory of Justice”. Revised Edition. Belknap Press

[3] Bird-Pollan (2013): “Unseating Privilege: Rawls, Equality of Opportunity, and Wealth Transfer Taxation”, 59 Wayne L. Rev. 713 (2014).

[4] Bird-Pollan (2013): “Death, Taxes and Property (Rights): Nozick, Libertarianism, and the Estate Tax”, 66 Me. L. Rev. 1 (2013)