All families are created equal? Individualism vs. Feudalism

In debates about inheritance, you can discover that disagreement about inheritance matters often boils down to disagreements about the ideological underpinnings. With this, I don’t refer to the potentially clear case of “left” vs. “right”, but to the slightly subtler issue of liberal individualists vs. those who may be called family-collectivists.

Why does the family matter?

Family-collectivists regard the family (in the nuclear type of parents and children or the extended type of the larger family of cousins, uncles and aunts, grandparents, etc.) as a valid subject entitled to rights and worth being protected. When arguing for equal opportunities of individuals and criticising inheritance as an obstacle to this, family-collectivists will be irritated by your focus on the individual and the ignorance of the family ties. Attempting to treat two people equally by not allowing any inheritance to skew their equal opportunities disregards the fact that they are from different families after all. In their view, families need to be treated equally rather than individuals. They see an intrinsic value in the collective unit of a family and seek its goals to be prioritised over those of the individuals.

Sometimes, the family is seen as an economic unit with collective ownership of all property. Value is ascribed to the multi-generational achievements in developing property, business, networks, reputation, etc. Family-collectivists stress the importance of the family even for individualists, or better: for the sound development of individual human beings. Families thus deliver what has been dubbed “family goods” by some, an essential function to society. Family-collectivists can see virtue in inheritance to the extent that it expresses an act of giving and caring to your family members. Some go so far as to say that children represent an extended part of parents’ identity, and inheritance is a means to strengthen this extended part of your identity.

A pretty powerful argument relates to every human’s sense of belonging and need for continuity, which families may quite well provide. Inheritance, in this light, can strengthen the ties between generations and manifest the continuity over generations in a very physical and concrete way. Handing over generation-old physical property such as houses, art, furniture and other precious goods such as jewellery may symbolise this continuity particularly well. Even immaterial property such as money in the bank can be associated with continuous power and a particular lifestyle with access to money-dependent networks that again symbolise and manifest continuity. Inheritance can thus provide a sense of belonging, as it emphasises your link to a chain of ancient family relations. You are part of something. You have a home, a history, a meaning.

But it does not need to be backwards-looking. It may even provide direction and guidance for the future. If your family has been active in a specific industry for ages or managing its forests, farms, or family businesses, your destiny and call may be much more apparent to you than if you’d disregarded all your family ties and had to find your purpose and direction in life without it. Similarly, but not quite as powerful, it can be argued from this stance that the long-term, century-spanning actions and impacts of families provide a more meaningful entity than a single individual. Disregarding family ties, from this perspective, may overrate the individual as a selfish and narcissistic figure.

Finally, there are also arguments of purely instrumental and economic nature, which stress the incentive value of being able to bequest your wealth to the next generation. If inheritance was banned, people would either work less (lower GDP) or spend more (less investment, higher consumption ratios). Both are judged as detrimental to economic development from this view. In the context of a family, this line of argumentation may also be linked to what we described earlier as the family providing meaning to your life. Taken both views together, because it’s possible to inherit wealth, it’s worth devoting your life to the creation of this wealth, thereby contributing to something as meaningful as your family.

Family-Collectivism as Feudalism

It seems clear from the above that there are good reasons to argue for the importance of the institution of the family, the value of family ties and the meaning and purpose it can give. It may also have become clear how, in a second step, family-collectivist arguments can be used in an attempt to justify inheritance. The interesting question is: is this a convincing story? To analyse this, let’s rephrase:

Hypothesis A: The family is important and provides meaning and value.

Hypothesis B: Because inheritance plays a strong role in intergenerational family ties, any attempt to tax inheritance is damaging the family and thus bad.

Hypothesis A, given the above thoughts and arguments, sounds convincing. Hardly anybody would argue for forbidding family life and having the state raise children straight after birth, not allowing any family relationships ever to arise. Nobody wants that.

Hypothesis B, however, is not convincing. We may well envision a rich family life and history with strong family ties that create meaning and satisfy the need for belonging and continuity without inheritance playing any role here. This could be the case for a rich family in a political setting where inheritance is illegal, or it could be the case for a poor family in which inheritance doesn’t play any role no matter the political setting. In both cases, some central elements and values of the family can well be conceived without inheritance. Taxing or even confiscating inheritance does not hinder family activities at its core: raising children, nurturing them, caring for other family members, all that does not require tax-free unlimited bequests. Even family-business succession is possible without tax-free wealth transfer to the next generation: shares can be bought and/or inheritance tax on the business property can be paid back to the state via a low to zero-interest, long-term tax loan.

How about the ownership question? Do families own property and is taxing inheritance thus taking away rightfully-owned property from those who would just want to take over the legal ownership from the deceased? This may have been a credible storyline a few hundred years ago in agricultural societies where families worked together on one farm, but with the modern-day division of labour and individuals taking up careers unrelated to their parents, there is no strong argument to be made that there is something like a family property that is collective because its collectively generated, or maintained, or looked after.

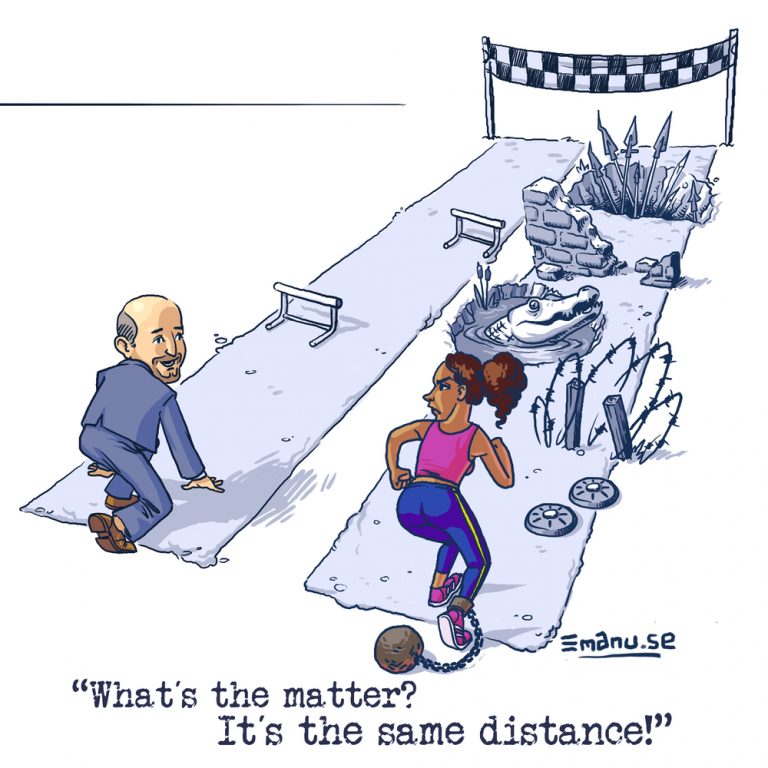

As for the question of whether inheritance can be seen as a source of virtue, this must be denied in many cases. Statistically, it does increase the chance of families ending up in court fighting over inheritance issues, and it can create spoiled children who lead unhappy, idle and unproductive lives. Also, even where inheritance may actually be beneficial (to your children), this always comes at the cost of harming those other children who did not get that extra start position in life. They will – in the race of life for education and careers – fall behind. The argument of ” inheritance as caring for your children” suffers from the fact that most bequests happen to grown-up children who don’t need that extra support anymore and can already be regarded as individual, autonomous members of society (which are still very much allowed and encouraged to have non-financial social ties to their family).

If few of the above arguments in favour of inheritance hold, how about the economic effects? Isn’t it a no-brainer that banning inheritance takes away one of the main motivations of humans to work and save? Well, as convincing this argument sounds, and as popular as it is, scientific research is inconclusive at most. If any significant effects of allowing or banning inheritance can be found at all, they are only very small. People. it seems, work and save and consume due to other motives than leaving fortunes to their children. They may work, because they like working, and they may save and not consume everything because they don’t gain much higher utility from consumption after a certain level of satisfaction. Actually, not very surprising, if you look at it from this perspective. Still, these scientific findings are quite the opposite of what is commonly assumed.

No matter whether small incentive effects may exist or not, there is a good reason not to accept the incentive argument to justify inheritance: In times of climate crisis and a growing awareness that there are planetary boundaries to economic growth, any argument that assumes “working more” and “investing more” is inherently a good thing is not convincing and must be regarded as outdated reasoning. For most of the 20th century since Simon Kuznet invented the measure of GDP in the 1930s, winning a debate by dropping the “this is bad for growth” argument did usually work fine. In the 21st century with the climate crisis becoming more severe every day, such simple lines of argumentation don’t hold. As long as each Euro of GDP has an environmental footprint, economic growth can not be our prime goal anymore. From this perspective, slightly reduced incentives to accumulate wealth (which science can’t find strong evidency for, see above) would even help taking out some of the growth pressures that drove us into the dangerous situation we are in.

The family is good, yet inheritance remains problematic

In short: Yes, there is value in the family, but inheritance is by no means a necessary condition for all the virtues of family ties. And even in the few cases where inheritance may indeed strengthen family ties, the huge damage it creates in terms of being the strongest driver of unequal opportunities outweighs the advantages by far. Lastly, we have identified cases in which inheritance actually damages family relations.

Now: what to conclude? If we follow Wikipedia (and through it Adam Smith) on one definition of feudalism as

“a social and economic system defined by inherited social ranks, each of which possessed inherent social and economic privileges”

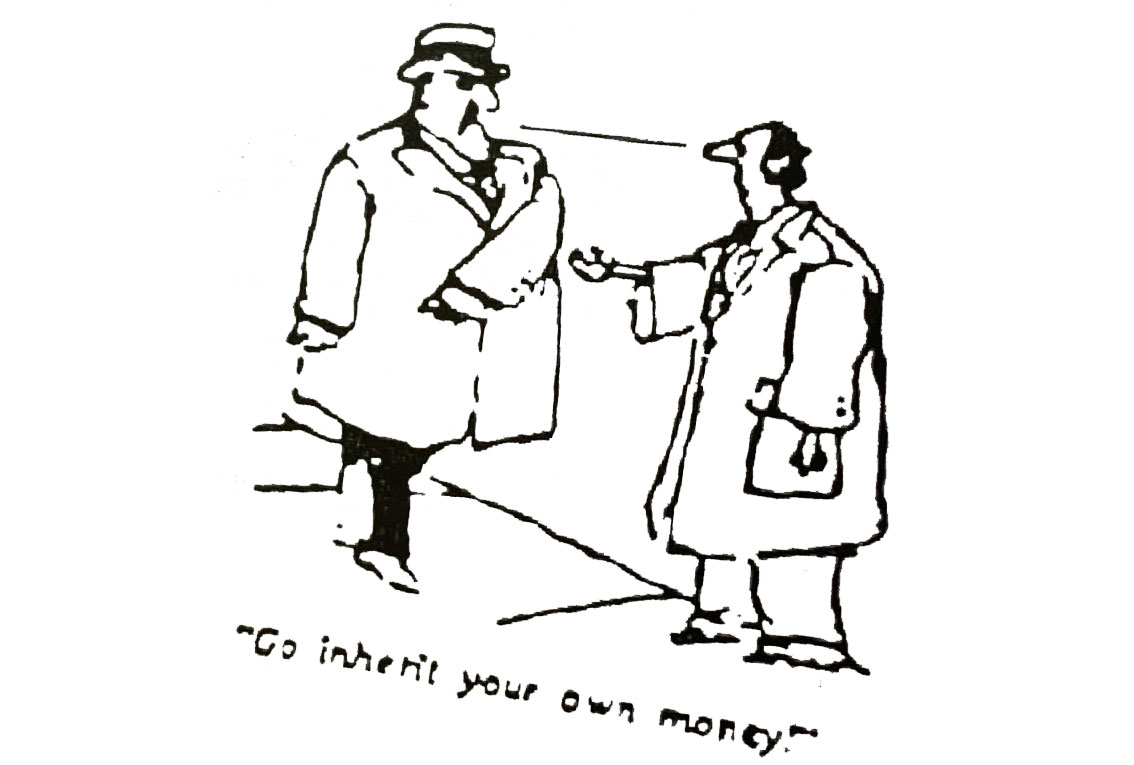

we can see why a form of family-collectivism that defines itself heavily through unhindered inheritance flows may well be termed family-feudalism. Inheritance and privileges are two sides of the same coin. For a society in which all (wo)men are born equal, we need to overcome family-feudalism just as much as we had to free ourselves from historical feudalism back a few centuries.

Further Reading

- Löschke and Brighouse, 2016: Family Values: The Ethics of Parent-Child Relationships ; http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt7ztpk2

- Pedersen and Boyum, 2019: Inheritance and the Family; https://doi.org/10.1111/japp.12389

Image Source

unknown (if you know, please drop us a message so we can credit)