Biologocial Feudalism

Biological Feudalism

Privilege can not only be passed on through economic or sociocultural channels, but also much more directly and fundamentally by biological means. The development of personal abilities and potential is influenced by a complex interplay of biological factors. These factors operate across the lifespan, shaping cognitive, physical, and emotional capacities. Understanding the biological determinants of development through the lens of social justice and equality of opportunity highlights how some individuals inherit not only genetic traits but also epigenetic and environmental advantages or disadvantages. These inherited influences can perpetuate social inequality, despite efforts to create equal opportunities. In this chapter, we will explore six major categories of biological determinants and examine how they intersect with economic and socio-cultural inheritance of privilege. As this book focusses on economic inheritance, this section (much like the socio-cultural) will remain on the surface and only attempt to give a glimpse into the subject, hopefully enough to understand the relevance for economic inheritance and equality of opportunity as a whole.

Overview of biological determinants

1. Genetic Determinants

Genetic determinants refer to the traits inherited through DNA from biological parents. These genes influence a wide range of characteristics, from cognitive abilities to physical aptitudes and susceptibility to certain health conditions.

Genetic traits create natural variations in abilities and potential, but they also interact with environmental conditions, making some individuals more adaptable to opportunities than others. While genetic inheritance is often seen as neutral in discussions of fairness, it can amplify social inequalities when combined with access to resources and opportunities.

Twin and adoption studies have been widely used to estimate the heritability of traits like intelligence. Research suggests that intelligence is highly heritable, with estimates suggesting around 50% of intelligence to be explainable by genetic factors.[1] However, the degree to which genetic potential is realized depends heavily on environmental factors, reinforcing that genetics alone do not account for observed differences in achievement. Other studies show that the heritability of intelligence is significantly lower in low-income environments, indicating that social conditions constrain genetic potential.[2]

2. Inherited Epigenetic Determinants

Epigenetic determinants involve changes in gene expression that are passed from parents to offspring. These changes do not alter the DNA sequence itself but influence how certain genes are activated or silenced. Epigenetic changes can be shaped by the parents’ life experiences, including their exposure to stress, diet, and social conditions.

The inheritance of epigenetic traits reflects a form of biological privilege or disadvantage that is intricately linked to socio-economic status. Parents who experience significant social or economic stress may pass down epigenetic modifications that affect their children’s resilience, stress response, and cognitive abilities. This biological inheritance can perpetuate cycles of disadvantage, making it increasingly difficult for families with fewer resources to escape poverty. For example, a parent who faced chronic food insecurity might pass on epigenetic markers that affect how their child’s body metabolizes food, compounding health disparities and limiting academic and professional success.

A landmark Dutch Hunger Winter study provides compelling evidence of transgenerational epigenetic inheritance. This study examined children born to mothers who experienced famine during pregnancy and found that these children had higher rates of metabolic diseases and other health issues later in life.[3] Other research shows that parental care, particularly maternal behavior, can influence epigenetic changes related to stress regulation in offspring, reinforcing the impact of early environmental conditions on biological inheritance.[4]

3. In Utero/Prenatal Epigenetic Determinants

During pregnancy, environmental factors such as maternal stress, nutrition, and exposure to toxins can cause epigenetic changes in the developing fetus. These prenatal epigenetic changes can have long-term consequences on a child’s development and future abilities.

In utero epigenetic modifications serve as a critical pathway through which inequality of opportunity is biologically entrenched. Pregnant individuals who lack access to healthcare, nutritious food, or stable housing are more likely to experience high stress levels or malnutrition, leading to epigenetic changes that may disadvantage their child before birth. This interconnection between maternal circumstances and fetal development highlights how socio-economic disparities can translate into biological disadvantages.

Research on the “fetal origins of adult disease” shows that adverse prenatal conditions, such as maternal malnutrition or stress, can lead to epigenetic changes that increase the risk of chronic diseases like heart disease and diabetes later in life.[5] Studies of prenatal stress found that children of mothers who experienced high levels of stress during pregnancy showed altered cortisol levels, indicating long-term changes in stress response pathways that can affect mental health and cognitive development.[6]

4. In Utero/Prenatal Non-Genetic Determinants

In addition to epigenetic changes, non-genetic environmental factors during pregnancy can directly affect fetal development. These factors include maternal nutrition, exposure to harmful substances (such as alcohol or drugs), infections, and overall health.

The prenatal environment creates developmental disparities rooted not in genetics but in socio-economic conditions. Families with fewer resources may struggle to afford prenatal care or live in environments where exposure to environmental toxins is more likely. This link between socio-economic status and prenatal health conditions can severely hinder a child’s development. For instance, pregnant individuals from low-income communities may face higher levels of air pollution, inadequate access to clean water, or food deserts, leading to higher rates of premature birth or developmental delays. These challenges put children at a disadvantage, limiting their opportunities long before they enter school.

A well-known study on fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS) highlights how maternal consumption of alcohol during pregnancy can lead to severe developmental disabilities in children. It was found that children with FAS experience cognitive and behavioral challenges that limit their ability to succeed academically and socially.[7] Furthermore, studies on maternal malnutrition show that inadequate nutrition during pregnancy can lead to stunted growth and impaired brain development in children, contributing to intergenerational poverty.[8]

5. Postnatal Epigenetic Determinants

After birth, environmental influences continue to shape gene expression through epigenetic mechanisms. These influences include childhood nutrition, social relationships, stress levels, and exposure to educational resources.

Postnatal epigenetic changes highlight the ongoing impact of socio-economic status on a child’s development. Children born into wealthy, supportive environments are more likely to experience positive epigenetic effects that enhance their ability to succeed in school and social settings. In contrast, children facing neglect, malnutrition, or chronic stress may develop negative epigenetic changes that impair their emotional and cognitive functioning, limiting their capacity to seize available opportunities. A child raised in a stimulating environment may develop epigenetic changes that enhance learning and memory, while one in a neglectful environment may have their cognitive and emotional development stunted, further entrenching social inequalities.

Research on the epigenetic effects of childhood abuse shows that early-life stress can lead to epigenetic changes that affect the brain’s response to stress, increasing the risk of mental health issues later in life.[9]

6. Postnatal Non-Genetic Determinants

Non-genetic determinants in the postnatal period include environmental, social, and cultural factors that shape a child’s development. These factors, such as the quality of education, social support, healthcare access, and exposure to trauma or enrichment, directly influence a child’s potential without altering their genes or gene expression.

Social inequalities significantly impact these postnatal determinants, creating disparities in opportunities that affect biological development. Children from privileged backgrounds typically benefit from high-quality educational resources and supportive environments, while those from disadvantaged backgrounds face numerous barriers. The biological transmission mechanisms at play include the effects of caregiver stress on children. For instance, elevated cortisol levels in caregivers can disrupt a child’s stress response systems and neurodevelopment. Conversely, enriching and securely-attached environments promote healthy neural connections, enhancing cognitive function and emotional regulation.[10] A child from a wealthy family might thrive from secure family attachments, a high-quality preschool and access to good healthcare, leading to better academic and emotional outcomes. In contrast, a child from a low-income family may struggle from neglect or trauma, enjoy less optimal education and childcare in underfunded schools and face health challenges, hindering their cognitive and social development. This highlights how non-genetic determinants can perpetuate social inequalities through their biological impacts.

| Determinant Category | Definition | Influence on Development |

| Genetic Determinants | Inherited traits encoded in DNA from biological parents. | Creates natural variation in cognitive, physical, and emotional abilities. |

| Inherited Epigenetic Determinants | Epigenetic changes passed down from parents affecting gene expression. | Influences stress resilience, health outcomes, and cognitive ability. |

| In Utero/Prenatal Epigenetic Determinants | Epigenetic changes during pregnancy caused by maternal stress, nutrition, etc. | Long-term impact on stress regulation, health, and cognitive development. |

| In Utero/Prenatal Non-Genetic Determinants | Environmental factors during pregnancy (nutrition, toxins, etc.) affecting fetus. | Direct developmental effects, leading to physical and cognitive deficits. |

| Postnatal Epigenetic Determinants | Environmental factors after birth that modify gene expression. | Impacts emotional regulation, stress response, and cognitive abilities. |

| Postnatal Non-Genetic Determinants | Environmental, social, and cultural factors after birth. | Directly influences cognitive, physical, and emotional development. |

Table 1: Biological determinants of privilege transmission & their relation to sociocultural and economic transmission factors.

Discrimination and Biological Reproduction of Privilege

Discrimination plays a significant role in the biological reproduction of inequality by intersecting with the biological determinants discussed in the text. Gender, skin color, neurodiversity, and disability can amplify the effects of these determinants, further entrenching social inequalities. As an example, recent research highlights the profound impact of race on inherited inequality. A study on data from South Africa, which is recognized as one of the world’s most unequal countries, reveals that almost three-quarters of the current inequality in South Africa is inherited from predetermined circumstances, with race being the most significant factor.[11] Parental background also plays a crucial role in perpetuating these inequalities. This underscores how systemic racial discrimination not only affects individuals in the present but also embeds itself in the societal structure, limiting opportunities across generations. The following sections give a rough overview of how discriminatory factors intersect with biological reproduction of privilege:

Genetic Determinants

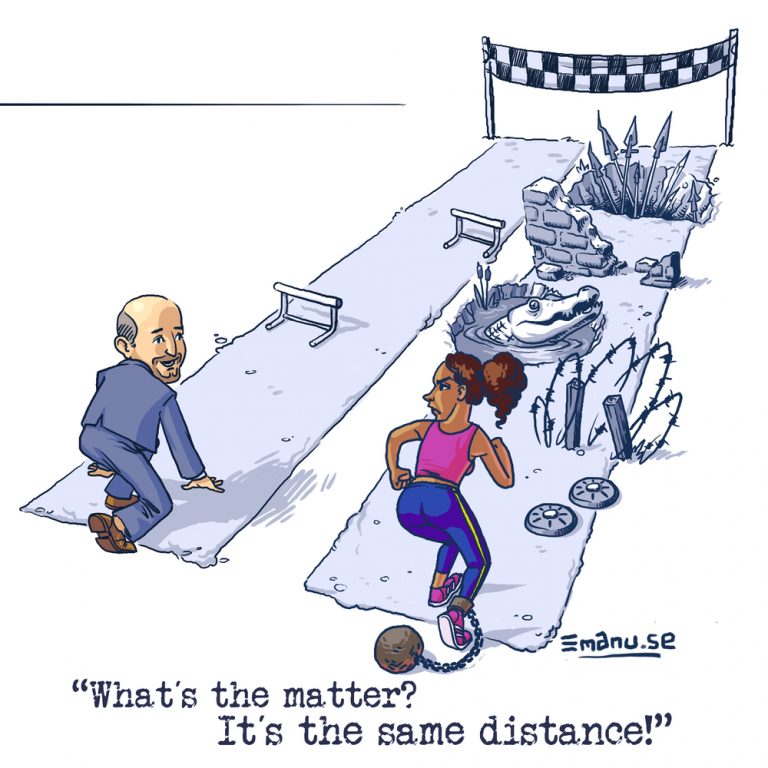

While genetic traits may be neutral in themselves, the intersection of skin color, gender, neurodiversity, and disability with social conditions can exacerbate the impact of genetic potential. For example, women, racial minorities, or people with disabilities often face systemic barriers that prevent them from accessing the resources necessary to fully realize their genetic potential. Thus, while genes may be inherited, the opportunities to develop them are not distributed equally, with discrimination limiting access to education, healthcare, and employment opportunities.

Epigenetic Determinants

Epigenetic changes influenced by socioeconomic status can disproportionately affect marginalized groups, as stress and adverse conditions—such as racism, sexism, or ableism—are more prevalent in their lives. Chronic stress from discrimination can lead to epigenetic modifications that negatively impact health and cognitive development, which can be passed on to future generations. For instance, women of color may experience both racial and gender discrimination, increasing their stress levels during pregnancy and influencing epigenetic changes in their offspring, perpetuating cycles of disadvantage. Additionally, neurodiverse individuals may face stigma and misunderstanding, contributing to stress that can also affect epigenetic expression.

In Utero/Prenatal Determinants

Pregnant individuals from marginalized groups are more likely to experience adverse conditions—such as lack of access to prenatal care or higher exposure to environmental toxins—due to systemic discrimination. This disproportionately affects women of color, those with disabilities, or those living in poverty. The heightened risks during pregnancy, such as increased maternal stress from racial discrimination, can cause epigenetic changes that limit a child’s potential, further embedding inequality into the biological development of future generations.

Postnatal Determinants

After birth, discriminatory practices can influence the environment in which a child develops. For example, racial segregation in housing or educational inequality based on socioeconomic status often leaves marginalized children in environments that lack access to quality education, healthcare, and safe living conditions. Such environments can lead to negative epigenetic and non-genetic outcomes, limiting cognitive, emotional, and physical development, particularly among racial minorities, women, and children with disabilities.

In summary, discrimination on the basis of skin color, gender, neurodiversity, and disability interacts with biological determinants of inequality by shaping the environments and stressors to which individuals are exposed, influencing both genetic expression and non-genetic development. These inherited biological effects reinforce social inequalities across generations, making it even harder for marginalized groups to escape systemic disadvantage.

Nature vs. Nurture

The debate between nature and nurture has long shaped discussions of human development, particularly in understanding how privilege and inequality are passed from one generation to the next. Is an individual’s potential primarily the result of biological inheritance (nature), or does the social and environmental context (nurture) play a more significant role? In the context of Biological Feudalism, this debate becomes critical to understanding whether efforts to equalize opportunity can truly succeed—or whether inherited biological factors will always give some individuals a natural advantage.

In this chapter, we will examine these two sides of the debate through the perspectives of two influential thinkers: Gregory Clark and Florencia Torche. Clark, whose work emphasizes the overwhelming role of biology in determining life outcomes, represents the “nature” side of the debate. Torche, who highlights the significant role of environmental and social factors, argues that “nurture” has a profound influence on individual potential, even at the biological level. By comparing these two positions, we aim to understand which offers a more convincing explanation of how privilege is transmitted and, ultimately, how inequality can be addressed.

The Case for Nature: Gregory Clark

Gregory Clark’s research, particularly in The Son also Rises, positions biology as the predominant factor in determining life outcomes.[12] He argues that traits such as intelligence, personality, and even social behavior are overwhelmingly shaped by genetics, and that these biological factors have a greater impact on an individual’s success than the environment they are raised in. Citing adoption studies, Clark concludes that outcomes for adopted children tend to correlate more closely with their biological parents than their adoptive ones, suggesting that genetic inheritance is the driving force behind life outcomes. In his words, “biology may not be everything, but it is the substantial majority of everything.”

Clark’s position on nature aligns closely with the concept of Biological Feudalism, where privilege is inherited not just through wealth or social status but through the biological traits passed down from one generation to the next. He suggests that no matter how much society attempts to create equal opportunities through education, welfare programs, or affirmative action, biological inheritance will still lead to unequal outcomes. In this view, the limits of social mobility are set by genetic inheritance, and while environmental factors may influence outcomes to some extent, they are far less significant than nature.

Clark’s argument raises a challenging question: if biological inheritance is the dominant factor, can true equality of opportunity ever be achieved? His findings suggest that, despite the best efforts of policymakers and social reformers, the persistence of genetic advantages and disadvantages will always result in unequal outcomes. In this view, privilege is biologically entrenched, and efforts to level the playing field will have limited imact.

The Case for Nurture: Florencia Torche

Florencia Torche, by contrast, offers a powerful argument for the importance of nurture.[13] Her work emphasizes that while genetic factors do play a role in individual development, the environment in which a person grows up profoundly shapes their abilities, health, and socioeconomic outcomes. Drawing on recent research in epigenetics, Torche demonstrates how environmental conditions—especially those experienced in early childhood—can alter gene expression in ways that affect long-term development. Poverty, stress, nutrition, and social support all contribute to shaping an individual’s potential, and these environmental factors are deeply intertwined with socioeconomic status.

Torche argues that the effects of nurture are so significant that they can blur the lines between biological inheritance and environmental influence. For instance, prenatal stress or poor nutrition—common among low-income populations—can lead to epigenetic changes that resemble genetic disadvantages but are, in fact, the result of environmental conditions. These epigenetic changes can affect cognitive development, stress resilience, and health, which in turn influence socioeconomic outcomes. According to Torche, this makes it nearly impossible to disentangle nature from nurture, as biological outcomes are so heavily shaped by social conditions. As she puts it, “This renders the distinction between endowment and socioeconomic constraints blurry to the point of being immaterial.”[14]

One of Torche’s most compelling insights is that inequality of opportunity is not just a matter of addressing genetic or biological differences; it requires addressing the structural socioeconomic factors that create and reinforce these differences. In her view, policies aimed at reducing inequality—such as providing better healthcare, early childhood education, and social support—can have a profound effect on leveling the playing field. This may be boiled down to a simple recipe: If you want equality of opportunity, create equality first.

Irrelevant Distinction?

In the end, Torche’s argument for the importance of nurture is more convincing in the context of social justice and equality of opportunity. While Clark’s biological determinism offers a sobering perspective on the limits of social mobility, it risks underestimating the power of social and environmental interventions to level the playing field. Torche’s emphasis on the profound impact of early childhood conditions, epigenetics, and social support provides a more optimistic and actionable framework for addressing inequality.

If we accept Clark’s view that biology is the dominant force in shaping outcomes, it leads to a more deterministic and potentially defeatist outlook on the possibility of change. However, Torche’s research offers hope that even deeply entrenched inequalities can be mitigated by improving the environments in which individuals develop. In this sense, the argument for nurture is not just more hopeful—it is more pragmatic, as it offers a path forward for reducing inequality through targeted policy interventions that can change not only social conditions but, ultimately, biological outcomes as well.

[1] See e.g. Plomin and Deary (2015): “Genetics and intelligence differences: five special findings” Mol Psychiatry 20, 98–108. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2014.105

[2] Turkheimer et al. (2003). “Socioeconomic status modifies heritability of IQ in young children. Psychol Sci. Nov;14(6):623-8. doi: 10.1046/j.0956-7976.2003.psci_1475.x. PMID: 14629696.

[3] Lumey et al. (2011): “Prenatal famine and adult health”. Annu Rev Public Health. 2011;32:237-62. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031210-101230. PMID: 21219171; PMCID: PMC3857581.

[4] Meaney and Szyf (2005): “Environmental programming of stress responses through DNA methylation: life at the interface between a dynamic environment and a fixed genome”. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2005;7(2):103-23. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2005.7.2/mmeaney. PMID: 16262207; PMCID: PMC3181727.

[5] Calkins and Devaskar (2011): “Fetal origins of adult disease”. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2011 Jul;41(6):158-76. doi: 10.1016/j.cppeds.2011.01.001. PMID: 21684471; PMCID: PMC4608552.

[6] Oberlander et al. (2008): “Prenatal exposure to maternal depression, neonatal methylation of human glucocorticoid receptor gene (NR3C1) and infant cortisol stress responses.” Epigenetics. 2008 Mar-Apr;3(2):97-106. doi: 10.4161/epi.3.2.6034. PMID: 18536531.

[7] Streissguth et al. (2004). “Risk factors for adverse life outcomes in fetal alcohol syndrome and fetal alcohol effects.” J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2004 Aug;25(4):228-38. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200408000-00002. PMID: 15308923.

[8] Black et al. (2013). “Maternal and Child Nutrition Study Group. Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries.” Lancet. 2013 Aug 3;382(9890):427-451. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60937-X. Epub 2013 Jun 6. Erratum in: Lancet. 2013. 2013 Aug 3;382(9890):396. PMID: 23746772.

[9] McGowan et al. (2009): “Epigenetic regulation of the glucocorticoid receptor in human brain associates with childhood abuse.” Nat Neurosci 12, 342–348 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.2270

[10] de Mendonça et al. (2022): “Examining attachment, cortisol secretion, and cognitive neurodevelopment in preschoolers and its predictive value for telomere length at age seven.” Front Behav Neurosci. 2022 Oct 13;16:954977. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2022.954977. PMID: 36311861; PMCID: PMC9606391.

[11] Brunori et al. (2024): “Inherited Inequality: A General Framework and a ‘Beyond-Averages’ Application to South Africa.” IZA Discussion Paper No. 17203, https://ssrn.com/abstract=4926521

[12] Clark et al. (2014). “The Son Also Rises: Surnames and the History of Social Mobility.” Princeton University Press, 2014. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt5hhrkm

[13] See Torche and Corvalan (2018): “Estimating Intergenerational Mobility With Grouped Data: A Critique of Clark’s the Son Also Rises.” Sociological Methods & Research, 47(4), 787-811. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124116661579

and Torche (2015). “Intergenerational Mobility and Equality of Opportunity”. European Journal of Sociology / Archives Européennes de Sociologie / Europäisches Archiv Für Soziologie, 56(3), 343–371. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26573215

[14] This view of a blurry distinction is also supported by other researchers, see e.g. Loi et al. (2013): “Social Epigenetics and Equality of Opportunity.” Public Health Ethics. 2013 Jul;6(2):142-153. doi: 10.1093/phe/pht019

One Comment