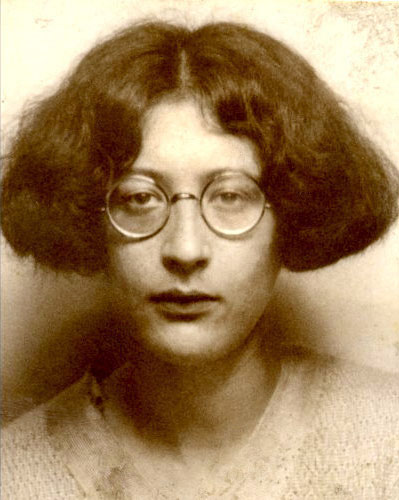

Simone Weil’s (1943) “right to property” against uprootedness

Simone Weil (1909–1943), was a philosopher who died working for the French resistance movement against Nazi-Germany. She is noted for her intense patriotism, Jewish heritage, and Christian spirituality, possessing a “great soul and brilliant mind” (in the words of T.S. Elliot). Weil’s political philosophy, as laid out among other works in The Need for Roots, frames social needs as duties owed to the human soul rather than as rights, which she considers subordinate and relative to obligations. Her specific proposals concerning property distribution outline a radical restructuring of capital access, closely related to the concept of a universal basic inheritance, designed to overcome the fundamental spiritual damage caused by modern industrial society.

Conception of Liberty

Weil defines liberty in its concrete sense as the real ability to choose. Crucially, she argues that liberty is only fully realised under specific social conditions. Liberty is complete when the rules governing society are sensible, straightforward, few in number, and stable, and the authority establishing them is embraced.

From a distributive perspective, Weil warns that when the possibilities of choice are so wide as to “injure the commonweal,” individuals are deprived of genuine liberty, leading to “irresponsibility, puerility and indifference” or anxiety. This implies that a just social order must structurally limit individual freedoms (such as excessive economic power or unlimited choices driven by the “hope of gain”) if those freedoms threaten the common framework necessary for the liberty of all members.

We can see that inherited wealth and its unequal distribution contradict Weil’s notion of liberty, so that is not surprising that she proposes some radical reforms towards the institution of property.

Importance of Property

Weil identifies property as an essential element of human nature:

“Private property is a vital need of the soul. The soul feels isolated, lost, if it is not surrounded by objects which seem to it like an extension of the bodily members. [,,,] where the feeling of appropriation doesn’t coincide with any legally recognized proprietorship, men are continually exposed to extremely painful spiritual wrenches.”[1]

She specifies that, ideally, the majority of people should possess “something more than the articles of ordinary consumption”, including their house and a piece of land around it, and, if technically possible, “the tools of their trade”. For peasants, this necessarily includes land and livestock. As an illustrative example, large agricultural estates owned by businessmen in cities but worked by labourers violate the principle of property, as no one connected to the land feels a sense of belonging. In addition to private ownership, Weil notes the importance of participation in collective possessions, a “feeling of ownership” in communal assets like public monuments, gardens, and ceremonies, which places “a display of sumptuousness… within the reach of even the poorest”.

Right to Property as a form of basic inheritance

Weil’s proposals effectively suggest a system of state-issued capital grant designed specifically to replace the “proletarian lot” and its defining characteristic: uprootedness. This proposed system is presented as being “neither capitalist nor socialist”. Weil seeks to abolish the distress among workers which creates “false problems” and “obsessions,” such as the intense fear of unemployment or the feeling of being “immigrants allowed to enter on sufferance” in the places they work. This plan is a method for “re-establishing the working-class by the roots”. The plan focuses on the dissolution of large factories and the distribution of assets necessary for independence.

The basic capital would be comprised of a “triple proprietorship comprising machine, house and land”. This proprietorship would be “bestowed on him by the State as a gift on his marriage,” conditional on the individual having successfully passed a examinations about technical skills, level of intelligence and “general culture”. We can see that Weil’s right to property is not fully universal or unconditional. Critically, Weil’s right to property is structurally non-inheritable and non-transferable. The property would be secured against transfer or sale, although the machine element alone could, under certain circumstances, be exchanged.

“On a workman’s death, this property would return to the State, which would, of course, if need be, be bound to maintain the well-being of the wife and children at the same level as before would return to the State, which would, of course, if need be, be bound to maintain the well-being of the wife and children at the same level as before”. [2]

Here, the social security function of private inheritance is replaced by a sort of state social welfare guarantee. However, Weil does allow for some form of private inheritance by viewing a nuclear family as an economic entity, so that “if the woman was capable of doing the work, she could keep the property”.[3]

On the question of financing and governance of the right to property, Weil holds

“All such gifts would be financed out of taxes, either levied directly on business profits or indirectly on the sale of business products. They would be administered by a board composed of government officials, owners of business undertakings, trade-unionists and representatives of the Chamber of Deputies.”[4]

It remains a bit unclear why tax financing is actually necessary for such a basic inheritance scheme, if property would fall to the state upon death.

Equality, Proportional Responsibility and Qualitative Differentiation

Equality is considered a vital need of the soul and consists in the public recognition that the “same amount of respect and consideration is due to every human being because this respect is due to the human being as such and is not a matter of degree”. To maintain balance between equality and inequality and prevent social decomposition, a “descending movement” must be ensured. Weil outlines this necessary equilibrium:

“To the extent to which it is really possible for the son of a farm labourer to become one day a minister, to the same extent should it really be possible for the son of a minister to become one day a farm labourer”.