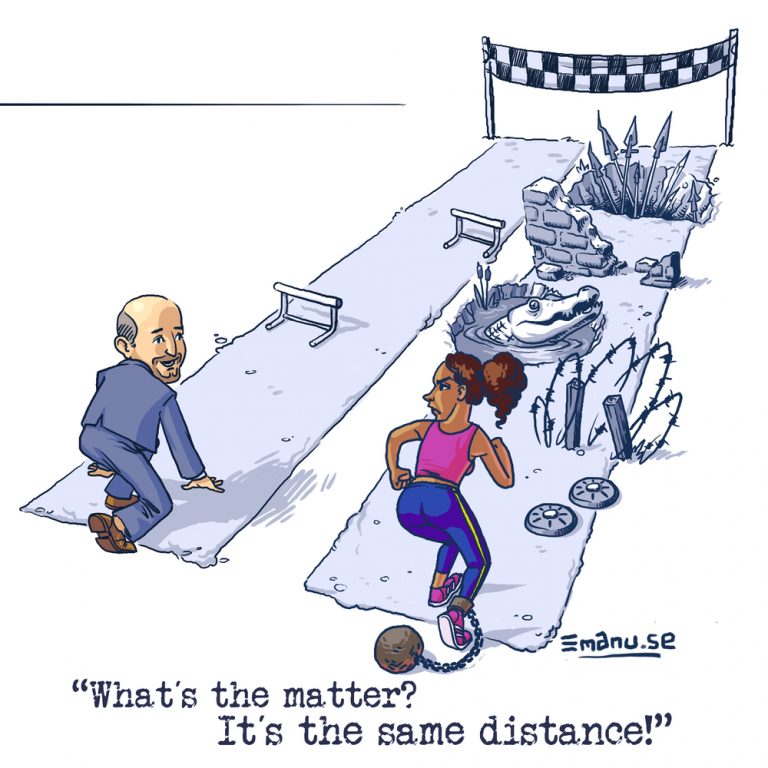

Inheritance as an equaliser?

Inheritance is sometimes touted as a mechanism that can reduce inequality by spreading wealth more evenly across society. This can technically be true, as there are a number of statistical mechanics at play. It doesn’t have to be like that, however. And as we shall see, it’s also a bit of a red herring in that it obscures the big picture, in which inheritance is, after all, not an equaliser. Let’s look at the matter through a few examples:

The mechanistic view

The spreading mechanism: If one person bequests to multiple others, wealth spreads out.

Inheritance can spread wealth among more individuals, potentially reducing inequality. Consider two families, each with three children. Family A is wealthy, with a parent having €3,000,000, while Family B is less wealthy, with a parent having €150,000. Before inheritance, each child has no wealth. If the wealth is evenly distributed among the children, Family A’s children each receive €1,000,000, and Family B’s children each receive €50,000.

Before inheritance, the Gini coefficient—a measure of inequality—was 0.86, indicating high wealth concentration in the parents. After inheritance, the wealth is distributed among more individuals, lowering the Gini coefficient to 0.59 and increasing the median wealth from €0 to €50,000. Although this shows a reduction in inequality, the absolute wealth gap remains significant (€1,000,000 vs. €50,000). This example highlights a key limitation: If we regard the family as a representation of a class[1], the inequality between the two classes remains unchanged.

Moreover, inheritance doesn’t necessarily “spread”. In shrinking societies where a wealthy couple leaves their entire estate to a single child, inheritance can actually increase inequality. Thus, the spreading mechanism is actually more a general “redistributive mechanism” that can work both ways: spreading wealth, or consolidating wealth, though it must be admitted that likely the former is more common.

Before

Inheritance/Gifting

|

|||||||

|

Family |

People |

Cum.

Population % |

Wealth (€) |

Cum.

Wealth % |

Area

Under Lorenz Curve |

||

|

0% |

|

0,0% |

|||||

|

B |

Child1 |

12,5% |

|

0,0% |

0,00 |

||

|

B |

Child2 |

25,0% |

|

0,0% |

0,00 |

||

|

B |

Child3 |

37,5% |

|

0,0% |

0,00 |

||

|

A |

Child1 |

50,0% |

|

0,0% |

0,00 |

||

|

A |

Child2 |

62,5% |

|

0,0% |

0,00 |

||

|

A |

Child3 |

75,0% |

|

0,0% |

0,00 |

||

|

B |

Parent |

87,5% |

150.000 € |

4,8% |

0,003 |

||

|

A |

Parent |

100,0% |

3.000.000 € |

100,0% |

0,065 |

||

|

Gini

Coefficient |

|||||||

|

0,86 |

|||||||

After

Inheritance/Gifting

|

|

|

|||||

|

Family |

People |

Cum.

Population % |

Wealth (€) |

Cum.

Wealth % |

Area

Under Lorenz Curve |

|

|

|

|

|

0% |

|

0,0% |

|

|

|

|

B |

Parent |

12,5% |

|

0,0% |

0,00 |

|

|

|

A |

Parent |

25,0% |

|

0,0% |

0,00 |

|

|

|

B |

Child1 |

37,5% |

50.000 € |

1,6% |

0,00 |

|

|

|

B |

Child2 |

50,0% |

50.000 € |

3,2% |

0,00 |

|

|

|

B |

Child3 |

62,5% |

50.000 € |

4,8% |

0,00 |

|

|

|

A |

Child1 |

75,0% |

1.000.000 € |

36,5% |

0,03 |

|

|

|

A |

Child2 |

87,5% |

1.000.000 € |

68,3% |

0,07 |

|

|

|

A |

Child3 |

100,0% |

1.000.000 € |

100,0% |

0,11 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Gini

Coefficient |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

0,59 |

|

|

Table 1: Inequality (as measured by

Gini coefficient) reduction through spreading effect.

The stabilising mechanism: If inequality is generally on the rise, inheritance can slow down this dynamic.

If inequality rises over time, inheritances can mitigate this effect by redistributing wealth accumulated in less unequal past generations. The wealth distribution of previous generations, which might have been more balanced, is passed on to the next, slowing the growth of inequality. There is some empirical evidence for this mechanism.[2]

In order to illustrate this, let’s revisit the family example above. Imagine the same financial situation of a poor and rich family, just with only one child each. Would the single parent of each family transfer all its wealth to its single child, the wealth distribution would remain unaffected. Wealth would just have passed from one generation to the next. There would be no spreading effect. The Gini coefficient would remain stable at 0.726.

However, if we allow for the more realistic assumption that the children have already advanced in life when the parent transfers the wealth (average age of inheritance is around 50 years in many countries), they already had the chance to save money from their jobs. Given the privileged background, the child of family A has already taken over leadership in the family business, accumulating wealth of 100k€ by savings from the salary. The child of family B, coming from humble backgrounds, didn’t manage to secure a job that pays much more than what is needed for living. All that is available is some 1k€ cash on the bank account. The Gini coefficient before transfer of inheritance in the children generation 0.49. Because inequality in the parent generation was lower (0.452), inheriting the parents wealth reduces the inequality in the children generation from 0.49 to 0.454.

In less technical terms, and closer the realities of many middle-class people, this effect is reflected in the following stylised quote, that can be heard quite often in this or a similar way: “Nowadays, it’s difficult for middle class people like me to accumulate a decent saving that would allow to build a house or buy a flat in a city. For my parents’ generation, it was normal to work, save and build a house. For my generation, without financial support from the parents, this model seems impossible nowadays.” Here, we see the stabilising effect of inheritance at play, in times of rising inequality. A formerly more equal distribution counterweighs the increasing inequality.

Importantly, it needs to be noted that the stabilisation mechanism can also work the other way around. In progressive societies with rising equality levels (as was the case in many western countries after the second World War), inheritances as a manifestation of the older status quo can slow down progress and make society less equal than it would be without it.

The proportional mechanism: Bequests benefit poorer households more than richer households.

Some studies state that bequests accrue disproportionally to the benefit of poorer households and thereby reduce relative wealth inequality.[3] To quote one study:

“As a proportion of their current wealth holdings, wealth transfers are actually greater for poorer households than richer ones. That is to say, a small gift to the poor means more than a large gift to the rich.”[4]

At first sight, this sounds like an independent mechanism different than the other two presented above. However, at closer inspection, it seems that the proportional and stabilising mechanisms are closely linked, and probably two-sides of the same coin. For wealth transfers to be proportionally larger for poorer households than for richer ones, this requires wealth inequality among the current wealth holders to be higher than in the previous generations (as manifested in the inheritance distribution). Thus, the proportional and stabilising mechanism can be regarded to be the same.

Why inheritance increases inequality after all

Inheritance can reduce inequality in specific cases, though this is not always the general rule When inheritance does reduce inequality, it is mainly due to technical factors. It reflects the mathematical redistribution of wealth rather than addressing the dynamic and structural inequalities in a stratified society. As we have seen the spreading/distribution as well as the stabilising/proportional mechanism can work both ways technically: increasing or decreasing inheritance.

Beyond the questionable validity of the forementioned mechanics, there are two further arguments to illustrate why inheritance doesn’t reduce inequality. Both are related to the counterfactual or alternative to inheritance. If we say “inheritance reduces inequality, this prompts the question: Compared to what alternative? No inheritance? What would that mean, exactly? Let’s consider two possible alternatives:

1) Abolishment of Inheritance through taxation, a 100% confiscatory inheritance tax. In the case of taxation, it is clear that the equalizing effect would then highly depend on what these taxes are used for. It is easy to imagine many ways in which such tax revenue could be used to decrease inequality: The most obvious solution would be a universal basic inheritance as a direct means of redistribution, but reductions in income tax for the middleclass or increased investments into education would be alternatives. We will turn to the most effective uses of inheritance tax revenue later. Here, it should be enough to note that the counterfactual to inheritance is hard to imagine without taxing inheritance and using the tax revenue for useful and inequality reducing purposes. Here, proponents of the view that “inheritance increases equality” would argue that the equalising effect comes from the usage of the taxation, not from the taxation and the implicit reduction of inheritance itself. This is correct, technically, though in practice the two things are so closely linked that it may be questionable how meaningful this objection is. The next argument will illustrate that the “inheritance increases equality” view is flawed irrespective of the usage of taxation.

2) Abolishment of inheritance without taxation: The key reason why “inheritance increases equality” is a flawed conception is that it is agnostic of the social realities that inheritance is embedded in. It is class-agnostic and not taking into account any of the social dynamics that shape wealth inequality. Let’s assume we didn’t have any inheritance. It would be abolished, simply not allowed. Property would be destroyed upon death, money burnt, bank accounts deleted. Without any taxation and redistribution, every generation would start afresh with perfect equality: everybody starts with nothing. Let’s call this world the equal opportunity world, compared to the current feudalistic world.[5] Differences in wealth can arise, of course, but only self-earned.

Measured against this alternative of full equality (of opportunity), neither the spreading nor the stabilising mechanism appears to be in favour of increasing equality. For the spreading effect, this is because it completely ignores if the spreading happens within a certain social class. The distributions as captured in the Gini are class and dynamism agnostic in the sense that two very different situations can hold the same degree of inequality, though its likely we would favour one over the other. Let us employ the example from above again. Because of our equal opportunity world, the financial situation of the children generation would be swapped. The children from humble background would become the richer ones, and vice-versa. The formal level of inequality as measured by the Gini would remain the same. However, from an equality of opportunity perspective the latter would really be a sign of social mobility where it is possible to climb the ladder even from humble backgrounds, whereas the original setup would be a sign of feudalistic inheritance of privilege. In the feudalistic world, it is doubtful how beneficial the effect of inheritance is if it spreads privilege from one very, very rich person to multiple very rich offspring. One could argue, that is even worse, because this offspring can now use the endowments to stabilise the advantages of its group or class. A truly beneficial “spreading” would be given if it would be random or reach everyone, like a universal basic inheritance. But in our feudalistic world, wealth doesn’t distribute randomly; it flows to heirs who are already advantaged through superior education, networks, and opportunities. Thus, wealth concentrated within privileged families continues to fuel their dominance across generations. Some self-made rich people have an instinctive aversion against such class formation through the spreading effect. They made it up against the privileged situation of others, and now they don’t want to create such unfair starting positions by overly endowing their children with an unearned income. Of course, other self-made wealth holders also fall for the opposite opinion: Because they had to fight themselves up, they want their children to have a smoother start in life, and don’t care if this means unequal opportunities for others.

For the sake of thoroughness, we should address one technical consideration that proponents of the idea of “inheritance reduces inequality” may bring up here, though it cannot directly be linked to the spreading or the stabilising mechanism. If, like theorised above, in our equal opportunity world we would have the situation of 100% social mobility in which the children from the humble family would make it to considerable wealth whereas the privileged children would fail to capitalise on their advantageous background, then inheritance could have a strongly equalising effect in this case. Inequality could be reduced significantly, because both children generations would be wealthy, instead of only the self-made one. So, in this case, inheritance would clearly reduce inequality. Full stop? Clearly no! While technically true, this type of equality is likely not what most people have in mind when lobbying for it. It would actually be closer to an equality of outcome model than an equality of opportunity model. It wouldn’t be conceived fair. If you come from privileged background, and you still failed to make something out of it, well then maybe it is really OK if someone who worked their way up is wealthier than you. It’s an acceptable or even desirable type of inequality, from a liberal perspective. Again, we come to see how a purely mechanical perception of the relation between inheritance and inequality can obscure the bigger picture.

As for the stabilising/proportional mechanism, it neither seems to stand the test against the equal opportunity world comparison. From the starting position of equal (financial) opportunity, it is not likely that the highly unequal distributions that we currently observe could develop only within a life-time as self-earned wealth. Not unless those from financially privileged backgrounds would enjoy substantial non-financial privileges that would be advantageous in the race of life and allow to secure higher positions and earnings despite not being able to directly inherit wealth. Otherwise, in the case of equal opportunities, we would assume that less unequal distributions would arise. Compared to this scenario, inheritance would increase inequality. The stabilising effect would reverse its direction. Or to put this in other words: The (inequality reducing) stabilising mechanism of inheritances depends on a higher inequality in the younger generations than the older. How, if not (at least partially) through non-monetary privileges (correlated with financial privileges) should such distributions have come about? If self-earned wealth is influenced by inherited wealth (already realised or expected), the net effect of inheritance on inequality is likely to be detrimental. If inherited privileges help individuals achieve higher self-earned wealth, the effect of inheritance might actually exacerbate inequality rather than reduce it. This is because those already benefiting from non-financial privileges may accumulate more wealth, further entrenching economic disparities. Non-financial inheritance, such as access to education, social networks, or familial support, can significantly impact individuals’ ability to earn wealth. This means that the effects of financial inheritance might be intertwined with these non-financial factors. There is also a kind of reverse correlation between self-earned wealth and inheritance. If course, how much I earn through my own work cannot really directly influence how wealthy my parents are and how much I inherit. However, my (self-earned) wealth level may influence how I use the inheritance that I get. Studies show that less wealthy heirs spend (as opposed to save and invest) a larger amount of their inheritance than wealthier heirs, increasing inequality (or diluting any potential equalising effect of inheritance).[6] If we link the two corrections above, the following story line appears: Coming from a privileged background, it is easy for me to build up my own wealth irrespective of any inheritance, and once I receive an inheritance, I can manage to save and invest most of it. A double negative effective of inheritance on equality that the purely technical viewpoint ignores entirely.

We come to see that self-earned wealth is not an exogenous factor, but endogenously influenced by inheritance and privilege in general. This includes the expectation of inheritance, which instates confidence and encourages risk-taking such as entrepreneurial activity. The next chapter will explore non-financial privileges in length. The point relevant here is that saying “inheritance reduces inequality” ignores the fact that this relies on a certain level of inequality in the younger generation that only a stratified, class-based society can produce. If we had abolished inheritance, over generations we would expect the class-based, non-financial privilege transmission to weaken and vanish. Important disclaimer: This does not mean there would be no inequality anymore, necessarily. It would likely be much lower, though. But more importantly: it would be a dynamically created inequality based on equal opportunities and social mobility, instead of a reflection of feudalistic handover of privilege within families across generations.

Summary

If we take all the above factors into account, it should have become clear that ultimately, inheritance may only technically reduce inequality in some few cases because it reproduces inequality in the first place. The net effect of inheritance remains detrimental to the case of equality of opportunity. This section was inspired by a researcher who advised me “I am sympathetic of inheritance tax, but I am against supporting it for the wrong reason. It doesn’t increase equality.” I believe he was wrong.

Notes

[1] By using class I do not implicitly reference any Marxian or related theories, but the mere general notion of the existence of different levels of wealth and opportunity which are fluid in theory, but in its stark differences to each other and low social mobility between them actually often somewhat rigid. This makes them analytical categories worth using as stylised groups of people in society.

[2] Elinder et al. (2018): Inheritance and wealth inequality: Evidence from population registers“. Journal of Public Economics. Volume 165, September 2018, Pages 17-30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2018.06.012

[3] Bönke et al. (2016): „How inheritances shape wealth distributions: An international comparison“. Economics Letters. Volume 159, October 2017, Pages 217-220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2017.08.007

[4] Wolff and Gittleman (2014): „Inheritances and the distribution of wealth or whatever happened to the great inheritance boom?“. J Econ Inequal 12, 439–468 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10888-013-9261-8

[5] It needs be noted that only abolishing financial privilege as incorporated in inheritance will not immediately result in a world of full equal opportunity, due to the many non-monetary privileges we shall look at in the next chapter.

[6] Elinder et al., ibid