Matthias Erzberger’s ambitious inheritance reform of 1919

Matthias Erzberger, a pivotal figure in early 20th-century German politics, stands out among proponents of inheritance reform due to his background as an active politician rather than an academic, and for having actually implemented his major tax reform proposals, at least for a short-while. His inheritance tax model, introduced in 1919 amidst Germany’s post-World War I financial turmoil, was found to be of “great technical beauty”[1] and possessed distinct particularities that merit its inclusion alongside the other theoretical frameworks presented here.

Background

Born in the small Württemberg village of Buttenhausen, the son of a tailor, Erzberger came from humble beginnings and lacked the formal higher education typical of the ruling elite, which often led him to be disdained as an “outsider”, an outsider who was later feared for advancing “the claims of men outside the charmed circle.”[2]

His early career involved teaching in the Württemberg school service, but his passion for political questions soon led him to journalism and the Catholic social movement. He became an editor at the Deutsches Volksblatt, a Stuttgart Catholic newspaper, and a leading figure in the Volksverein für das Katholische Deutschland, an organisation aimed at promoting the economic and cultural interests of Catholics and immunising them against Socialist agitation. As an “Arbeitersekretär” (secretary of the workers’ movement), Erzberger developed an encyclopaedic knowledge and capacity for rapid work, often providing comprehensive advice on workers’ rights and social legislation. He was also a prolific pamphleteer, known for his direct approach, comprehensive analysis, and unwavering conviction, notably in his polemics against Marxism and on subjects like militarism and religion.

Erzberger entered the Reichstag in 1903, where his “spectacular political rise”[3] began. He was a leading figure in the Catholic Zentrum party, becoming the leader of its democratic left wing. His political career was marked by his willingness to take on unpleasant tasks and his courage. During World War One, he rose to unprecedented prominence, managing Germany’s foreign propaganda and undertaking important diplomatic missions. He was a key actor in the July 1917 crisis, leading the Reichstag majority to adopt the Peace Resolution, advocating for a negotiated peace, and later signing the armistice ending the war on 11 November 1918. He was then appointed Finance Minister in June 1919, a role in which he initiated sweeping financial reforms. Erzberger loved responsibility and was driven by a buoyant, optimistic temperament, although his impulsiveness and indiscretion sometimes drew criticism. He came to symbolise the Weimar Republic to its enemies and was bitterly hated by nationalists, militarists, and conservatives, leading to his assassination in 1921.

Erzberger’s Silent Revolution

Upon assuming the role of Finance Minister on 21 June 1919, Erzberger faced a catastrophic financial situation in Germany. The national debt had ballooned from 5 billion marks in 1913 to 153 billion, with annual interest payments alone exceeding the entire peacetime budget.[4] Erzberger firmly rejected any notion of debt repudiation, arguing that it would unjustly penalise those who had supported the nation through war bonds while benefiting war profiteers and black marketeers. Instead, he advocated for confiscatory taxes upon the rich as a morally justified response to the scandalous failure to raise adequate taxes during the war. He believed his tax plans would not only prevent bankruptcy and restore financial order but also help build a genuinely democratic society where wealth was subject to sacrifice alongside labour, thereby diminishing the appeal of Bolshevism.[5]

Erzberger proposed and ultimately managed to pass through parliament a number of important tax reform bills that came to be known as the Erzbergersche Steuerreform. Among them, the inheritance reform stood out for its innovative design and bold scope. The German Reich Inheritance Tax Law (Deutsches Reichserbschaftssteuergesetz) of September 10th 1919[6] introduced three main forms of taxation related to inheritance:

- Estate Tax (Nachlasssteuer): This was a tax on the estate of the deceased. The tax was structured with progressive rates based on the value of the taxable estate starting at 1% and reaching 5% for estates beyond 2million Mark. This tax primarily had a control purpose. As it was put in the justification of an early bill draft: “If the testator failed to fulfil his tax obligations during his lifetime, the prospect of the entire estate having to be disclosed for review after his death, even before it is divided, is an effective psychological means of preventing tax evasion from the outset.”[7]

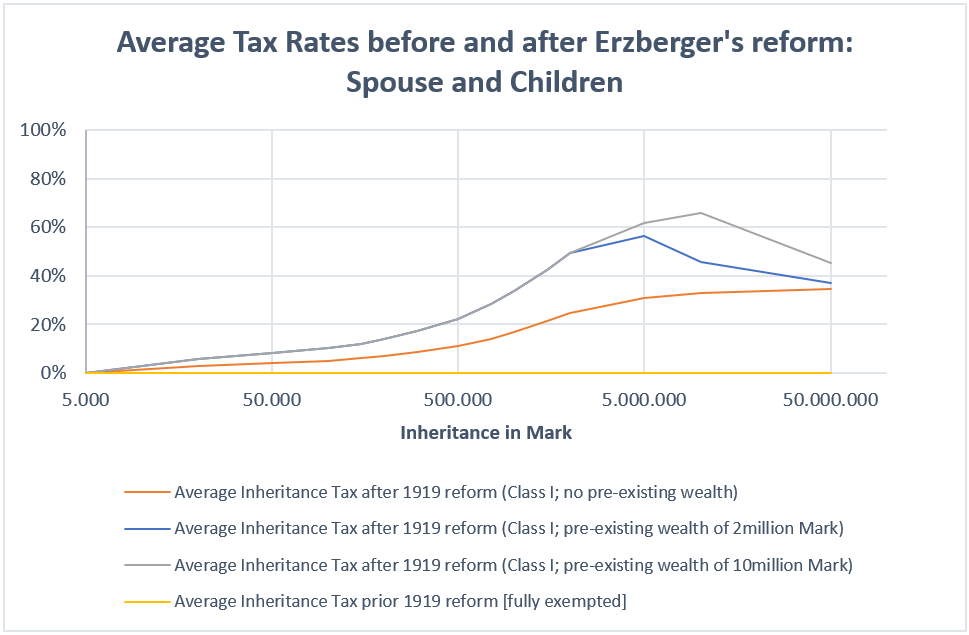

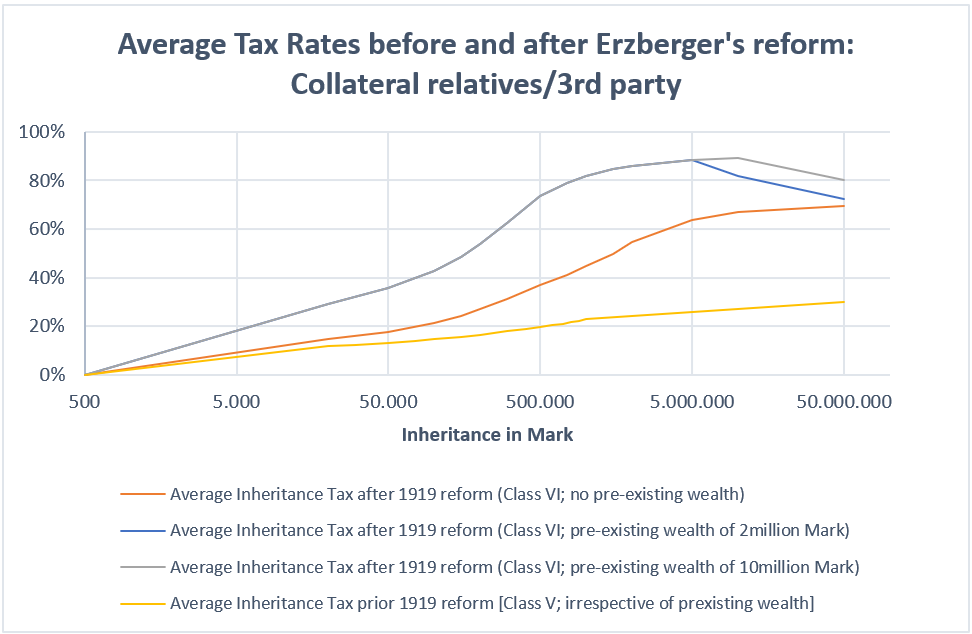

- Inheritance Tax (Erbanfallsteuer): This tax was levied on the acquisition of assets by the heir (Erwerb von Todes wegen). The tax rate was determined by the personal relationship of the acquirer to the deceased, categorised into six classes. Class I included the spouse and children, classes II to V were composed of grandchildren, parents, and further relatives up to the 4th degree; any collateral relative of further degree or 3rd parties were treated under Class VI. There was a tax-free threshold of 5000 Mark (approx. the same purchasing-power equivalent in EUR in 2024 money[8]) for children and most other heir groups, The inheritance tax rate ranged from 4% to 35% for Class I heirs and 15% to 70% for class VI heirs, depending on the size of the inheritance, the highest tax bracket being reached at 2million Mark (or EUR equivalent). The other classes’ tax rates lay between these rates. Exemptions and deductions were made for bequests towards the church or charitable purposes.

A unique feature of the inheritance tax was a surcharge that increased the tax amount based on the acquirer’s pre-existing wealth, effectively taxing bequests to the already well-off up to twice as high as those who haven’t yet made it to any riches, be it by inheritance or self-made wealth. The feature aimed to reduce excessive wealth accumulation and promote a more equitable distribution. However, it was also somewhat complex and the tax code not without ambiguity. The essential element was that the tax value itself increased by one percent of its amount (not of the inheritance amount) for every full or partial 10,000 M. by which the acquirer’s existing assets exceeded 100,000 M. but did not exceed 200,000 M. For existing assets exceeding 200,000 M., the surcharge was one percent of the tax for every full or partial 20,000 M. The surcharge was capped in multiple ways; it could not exceed half of the amount of existing assets that exceeded 100,000 M., nor could it be more than 100% of the tax itself, nor could the total amount of the inheritance tax (inheritance tax + surcharge) exceed 90% of the acquired inheritance. The first cap effectively made the inheritance tax regressive in nature, making sure the hefty maximum rates of 70% (for children/spouse) and 90% (for collateral/3rd party) would not apply to the very large fortunes, unless given to individuals already very wealthy.

- Gift Tax (Schenkungssteuer). This tax applied to gifts made between living persons, with identical tax rates to those of the inheritance tax.

Beyond the inheritance tax, Erzberger introduced other significant wealth-based taxes to complement his reform.

· A War Profits Tax (Kriegsabgabe) that targeted income increases over 1913 figures, affecting only the wealthy (starting at 13,000 marks income). Rates progressed up to 70 percent for millionaires and 80 percent for corporations, although this could be reduced to 40 percent in hardship cases.

· A War Surcharge on Capital Gains (Kriegsabgabe vom Vermögenszuwachs) that was applied to fortunes that had grown between 1 January 1914 and 30 June 1919. Progressive rates were applied, with increases exceeding 172,000 marks taxed at 100 percent, effectively setting a theoretical maximum on wartime profiteering gains. This tax aimed to collect 2 billion marks.

· A Sacrifice to the Reich in Its Hour of Need (Reichsnotopfer) This was a one-time capital levy designed to disproportionately affect the wealthy. While a married man with five children and a net worth of 30,000 marks might be exempted, the tax rate for those with 3 million marks could reach 50 percent of their capital. Payments were structured over thirty annual installments from 1920 to 1949 to prevent economic disruption.

The inheritance tax was discounted the first years to acknowledge the impact of these temporary war-related charges, and would have gradually phased in.

It needs to be noted that Erzberger inherited many of the fundamental elements of his tax reform from his predecessors in office as finance minister Eugen Schiffer and Bernhard Dernburg, as well as the “very able” state secretary Stephan Moesle.[9] However, Erzberger can be credited for fine-tuning and actually successfully bringing them through parliament. Also, if we compare the draft inheritance tax submitted by his predecessor Dernburg with the final bill that was enacted, we find that he managed to actually increase the tax rates even further and strengthen it.[10]

Erzberger’s inheritance reform was a radical one. The maximum possible marginal tax paid on bequests was 90,5% (estate tax and inheritance combined) for collateral heirs/3rd parties, and up to 71.5% for children and spouses. Despite the partially very high marginal rates, Erzberger initially expected a modest 700Million M. revenue from the inheritance tax, and thus only a 3% contribution to the total estimated budget of 25 billion M. Given inheritance tax revenue of around 70million in 1917[11] and a total estimated inheritance volume of 6 billion in 1911[12] the projected tax revenue can still be regarded as significant. The actual inheritance tax income of 1920 and 1921 fell a bit short of its projections, with 284 and 628 million M, respectively.[13] Given that the tax was only gradually phasing in due to reductions related to the temporary war-related taxes and contributions, it’s revenue potential would have increased in significance over time.

Because of capital flight[14], protest against the tax and the turbulences of the hyperinflation that Germany in 1922/23, Erzberger’s inheritance tax system was reformed multiple times until it had lost much of its confiscatory and unique character.[15] By 1925, top marginal tax rates for children were down to 15% again, the estate tax removed, and the tax surcharges based on pre-existing wealth abandoned as well. The expected inheritance tax returns accordingly fell from 700 million M and 3% of the state budget in 1920 to 34 million RM and 0,4% of the budget in 2026.[16]

Despite these challenges and the fierce opposition he faced, Erzberger’s inheritance tax and broader fiscal reforms remain the largest tax reform of younger German history and have shaped the tax system until the current day and like no other reform since.[17] Erzberger’s reforms initiated a constitutional revolution by establishing the fiscal sovereignty of the Reich, centralising tax collection and weakening the financial autonomy of individual states, serving as a “powerful rivet of the Reich” (Reichsklammer)[18]. Still, despite his enormous influence and important role in the Weimar republic, he is not very well known and remembered among the general German public.

References/Further Reading

[1] Epstein (1959): “Matthias Erzberger and the dilemma of German democracy.” Princeton University Press. p.341

[2] Ibid. p. 5

[3] Ibid. p. 46

[4] Ibid. p. 331

[5] Ibid. p. 334

[6] Deutsches Reichserbschaftssteuergesetz. Vom 10. September 1919. FinanzArchiv / Public Finance Analysis, 37. Jahrg., H. 1 (1920), pp. 315-331. Mohr Siebeck GmbH & Co. KG. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40906299 .

[7] Reichstagsprotokolle (1920). „Verhandlungen des Reichstages“ Bd.: 335. 1919/20, Berlin, 1920. „Entwurf eines Erbschaftssteuergesetzes: Begründung“. https://daten.digitale-sammlungen.de/bsb00000019/image_656

[8] Deutsche Bundesbank (2025). „Purchasing power equivalents of historical amounts in German currencies”. https://www.bundesbank.de/en/statistics/economic-activity-and-prices/-/purchasing-power-equivalents-of-historical-amounts-in-german-currencies-622372

[9] Ibid. p. 338

[10] Reichstagsprotokolle (1920). „Verhandlungen des Reichstages“ Bd.: 335. 1919/20, Berlin, 1920. „Entwurf eines Erbschaftssteuergesetzes“.https://daten.digitale-sammlungen.de/bsb00000019/image_641

[11] Statistisches Jahrbuch für das Deutsche Reich (1921/1922). Berlin . Schmidt. https://www.statistischebibliothek.de/mir/receive/DESerie_mods_00007448

[12] Schinke (2012): “Inheritance in Germany 1911 to 2009: A Mortality Multiplier Approach”. https://www.diw.de/documents/publikationen/73/diw_01.c.407138.de/diw_sp0462.pdf

[13] Statistisches Jahrbuch für das Deutsche Reich (1923). Berlin . Schmidt. https://www.statistischebibliothek.de/mir/receive/DESerie_mods_00007448

[14] As Erzberger’s biographer commented: “It is probable that Erzberger could have collected almost as much, and avoided the unfortunate consequences […], if he had set his tax rates substantially lower”. Epstein (1959), p.346

[15] Reiner Sahm (2012): „Zum Teufel mit der Steuer“. Springer. p. 272.

[16] Statistisches Jahrbuch für das Deutsche Reich (1928). Berlin . Schmidt. https://www.statistischebibliothek.de/mir/receive/DESerie_mods_00007448

[17] Bach (2018): „100 Jahre deutsches Steuersystem: Revolution und Evolution“. DIW Berlin. https://www.diw.de/documents/publikationen/73/diw_01.c.606752.de/dp1767.pdf

[18] Epstein (1959), p. 336